Long ago, in the lush valleys and misty mountains of Laos, there lived a young monk named Xieng Mieng. He was neither noble nor powerful, but his mind was as sharp as a blade and as light as a breeze. He was known throughout the land for his quick wit, playful humor, and gentle heart. Though humble in appearance, Xieng Mieng could outthink the proud, humble the arrogant, and reveal truth through laughter.

In those days, Laos was ruled by a powerful king whose palace gleamed with gold and whose pride gleamed even brighter. He was a man who loved riddles and challenges, yet could not bear to lose an argument. His courtiers always agreed with him, and none dared to correct his errors or question his decrees. Over time, the king grew vain, believing that his wisdom was beyond comparison.

One day, in a moment of boredom, the king proclaimed a new challenge to his court. “I have heard many tales of clever monks and wise men,” he said. “Let us see if any among them can make me laugh without speaking a single word. If someone succeeds, I will grant them gold and silk. But if they fail, they shall be punished for wasting my royal time.”

Discover more East Asian Folktales from the lands of dragons, cherry blossoms, and mountain spirits.

Word of the challenge spread quickly across the kingdom. Entertainers, scholars, and even wandering magicians came to the palace, eager for the reward. One by one, they performed tricks, dances, and pantomimes. Some stood on their heads, others juggled flaming torches or made funny faces. Yet the king remained unmoved. His face stayed cold and stern, and one by one, the performers left the court in shame.

In a small temple not far from the royal city, Xieng Mieng heard of the king’s challenge. The monks laughed when they heard it. “No one can make the king laugh,” they said. “He is too proud and too serious. Even a jester’s dance would not move his heart.”

But Xieng Mieng smiled quietly. “Perhaps,” he said, “the king has forgotten how to laugh because no one dares to show him the truth.”

The next morning, dressed in his simple saffron robe, he walked to the palace gates. The guards laughed when they saw him. “What can a poor monk like you do that the great performers could not?”

Xieng Mieng bowed respectfully. “Please tell your king,” he said, “that I wish to take part in his challenge. All I ask for is a brush, some ink, and a bowl of milk.”

The king, curious and slightly amused by the monk’s confidence, allowed him to enter the court. “Very well,” he said. “You may begin. But remember, if I do not laugh, you will be punished.”

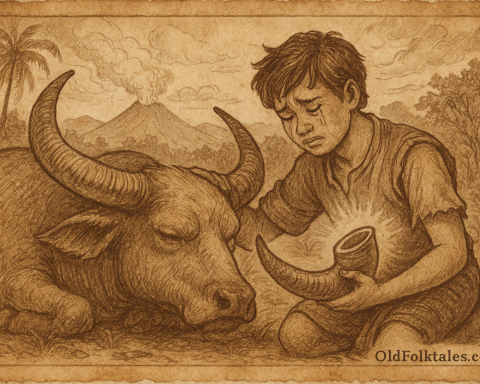

Xieng Mieng knelt on the floor, spread a piece of parchment before him, and dipped his brush in the ink. With calm strokes, he began to paint. The court fell silent as they watched the monk at work. Slowly, a picture emerged on the parchment: a plump, wide-eyed cat crouched before a bowl of milk. But in the reflection of the milk, instead of the cat’s face, there appeared the king’s own image, wearing a crown and looking both startled and foolish.

When Xieng Mieng finished, he held the painting up silently for all to see. For a moment, the court was quiet. Then one minister chuckled. Another snorted. Soon, the entire hall was filled with laughter. The proud king, who had never seen his own reflection in such a way, tried to resist, but at last, he too burst into laughter, a deep, honest laugh that echoed through the hall.

Wiping tears from his eyes, the king said, “Monk, you have succeeded where many have failed. You have made me laugh without a single word. Tell me, what lesson lies in this painting of yours?”

Xieng Mieng bowed. “Your Majesty,” he said, “sometimes wisdom hides behind a smile. When pride grows too tall, laughter cuts it down to size. I wished only to remind Your Majesty that even a king can be the cat chasing his own reflection.”

The king’s laughter faded into thought. For a long while, he looked at Xieng Mieng in silence. Then he said, “You are not only clever but wise. Tell me, monk, why do you spend your days in temples and jokes when you could use your wit to gain wealth and power?”

Xieng Mieng smiled gently. “Because, Your Majesty, power fades like a cloud, but laughter endures. A wise man does not need a throne to rule his mind, nor riches to fill his heart. My joy lies in teaching wisdom through laughter and truth through play.”

The king was moved by his words. “Stay in my court,” he said. “You shall be my counselor in matters of wit and wisdom.”

From that day forward, Xieng Mieng became a trusted advisor, though he was never too proud to jest with the king or challenge his thinking. Sometimes he would play small tricks to teach moral lessons. When the king grew arrogant again, Xieng Mieng would find gentle, humorous ways to remind him of humility. His humor softened the hearts of even the most stubborn courtiers.

One day, a foreign ambassador visited the palace, boasting of his knowledge and wealth. The king, proud of his new counselor, said, “If you can defeat my monk in a battle of wit, I shall reward you with gold. But if you lose, you must admit that Laos is the home of the wisest man.”

The ambassador agreed. “I will test him,” he said, “but the rule shall be that he cannot speak.”

The king nodded. “Then let it be so.”

The ambassador approached Xieng Mieng and lifted one finger, meaning “one.” Xieng Mieng lifted two fingers. The ambassador frowned and lifted three fingers. Xieng Mieng smiled and showed a closed fist.

The ambassador turned red, bowed, and admitted defeat. The court erupted in laughter. The king, confused, asked, “What just happened?”

The ambassador replied, “I showed him one finger to mean there is one God. He showed me two to say there are both God and man. I showed three to mean heaven, earth, and hell, but he closed his fist to remind me that all are one in the same universe. He is truly wise.”

But when the king turned to Xieng Mieng and asked the same question, the monk laughed and said, “He showed me one finger to threaten to poke my eye. I showed him two to say I would poke both of his. He showed three to say he would strike me thrice, so I made a fist to say I’d fight back!”

The court laughed even harder, and the king joined them. He realized that wisdom could wear many faces serious or playful, profound or simple and that Xieng Mieng’s humor was a mirror reflecting truth in its most human form.

Through the years, Xieng Mieng’s tales spread across Laos, told by elders at moonlit gatherings and by monks in quiet temples. He became a symbol of cleverness, humility, and the belief that laughter and kindness were stronger than pride or power. His tricks were not meant to humiliate but to enlighten, showing people that the mind is a sharper weapon than the sword.

Even today, Lao parents tell their children stories of Xieng Mieng before bedtime, teaching them to be brave, kind, and wise but never arrogant. For in the laughter of this simple monk lies the heart of Lao wisdom itself.

Moral Lesson

The story teaches that wisdom and humor are powerful tools against pride and injustice. True intelligence lies not in power or wealth but in the ability to think clearly, act kindly, and laugh at one’s own faults.

Knowledge Check

-

Who was Xieng Mieng?

He was a clever monk known for his humor and intelligence. -

What challenge did the king set?

He demanded that someone make him laugh without speaking. -

How did Xieng Mieng make the king laugh?

He painted a cat looking into a bowl of milk and reflecting the king’s face. -

What lesson did the monk teach the king?

That laughter humbles pride and opens the heart to wisdom. -

What did Xieng Mieng say about power and laughter?

He said that power fades, but laughter endures and brings truth. -

What is the main moral of the story?

Wisdom and humor can overcome pride and teach kindness.

Source

Adapted from The Tales of Xieng Mieng, collected and translated by Wajuppa Tossa and Kongdeuane Nettavong (1990), Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai.

Cultural Origin

Laos (Lao Buddhist folklore and oral storytelling tradition)