In the kampongs of Brunei, where rice fields stretch across the lowlands in neat geometric patterns and water buffalo rest in the shade of coconut palms, there once lived a man known to everyone as Si Paloian. His name was spoken with a mixture of affection and exasperation, for Si Paloian was clever, yes, but he was also reckless, impatient, and forever convinced that he could find easier ways to accomplish tasks that generations before him had done through patient, methodical work.

Si Paloian was not lazy, exactly. He was willing to work, but he wanted results immediately, and he chafed at the slow, careful pace required by traditional methods. While other farmers in his kampong followed the agricultural customs passed down from their ancestors, planting at the proper time, tending their fields with regular care, and harvesting according to the rhythms of the seasons, Si Paloian was always looking for shortcuts, for clever tricks that would allow him to get ahead faster than his neighbors.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

One year, Si Paloian decided he would cultivate his own padi field. His father had left him a small plot of land suitable for rice cultivation, and Si Paloian was determined to prove that his modern, innovative approach would yield a better harvest than the old-fashioned methods his fellow villagers insisted upon.

The planting season arrived with the monsoon rains, and the kampong came alive with communal activity. Farmers helped one another prepare their fields, plowing the mud with water buffalo, transplanting seedlings in careful rows, their backs bent under the hot sun as they worked in the flooded paddies. The work was hard and time-consuming, but it was also social, filled with conversation, laughter, and the satisfaction of shared labor.

Si Paloian participated in the planting, though he complained constantly about how long everything took. “Why must we plant each seedling so carefully?” he grumbled. “Why must the rows be so straight and evenly spaced? Surely the rice will grow just as well if we simply scatter the seeds and let nature take its course!”

The older farmers smiled at his impatience but said nothing. They had learned long ago that some lessons cannot be taught through words but only through experience.

As the growing season progressed, Si Paloian’s neighbors tended their fields with regular care. They walked through their paddies daily, checking water levels, pulling weeds, watching for pests, and ensuring that each plant had what it needed to thrive. They understood that rice cultivation is not a matter of planting and then waiting for harvest but requires constant attention and adjustment.

Si Paloian, however, found this routine tedious. He visited his field occasionally, but he spent most of his time sitting in the shade, thinking about how much rice he would harvest and how impressed everyone would be when his innovative approach proved successful. He convinced himself that his field looked fine, that the plants were growing well enough without all the fussy maintenance his neighbors insisted upon.

When weeds began to sprout among his rice plants, Si Paloian decided that pulling them individually was too time consuming. “I will cut them all down at once when the harvest comes,” he reasoned. “Why waste time pulling weeds now when I will be harvesting everything soon anyway?”

When the water level in his field dropped too low during a dry spell, Si Paloian told himself it did not matter. “Rice is a hardy plant,” he said. “It will adapt. My neighbors worry too much.”

When birds began to feast on the ripening grain in his field, Si Paloian waved them away once or twice but did not build the scarecrows or set up the noise makers that other farmers used to protect their crops. “There is plenty of rice,” he assured himself. “The birds cannot eat it all.”

Finally, the harvest season arrived. This was the time Si Paloian had been waiting for, the moment when his easier approach would be vindicated. He watched as his neighbors began harvesting their fields, cutting the rice stalks with small hand sickles, carefully gathering the grain, threshing it properly to separate the rice from the chaff. The process was slow and labor intensive, and Si Paloian shook his head at their old-fashioned methods.

“I will harvest my field much faster,” he announced proudly to anyone who would listen. “I have devised a superior method that will save days of work.”

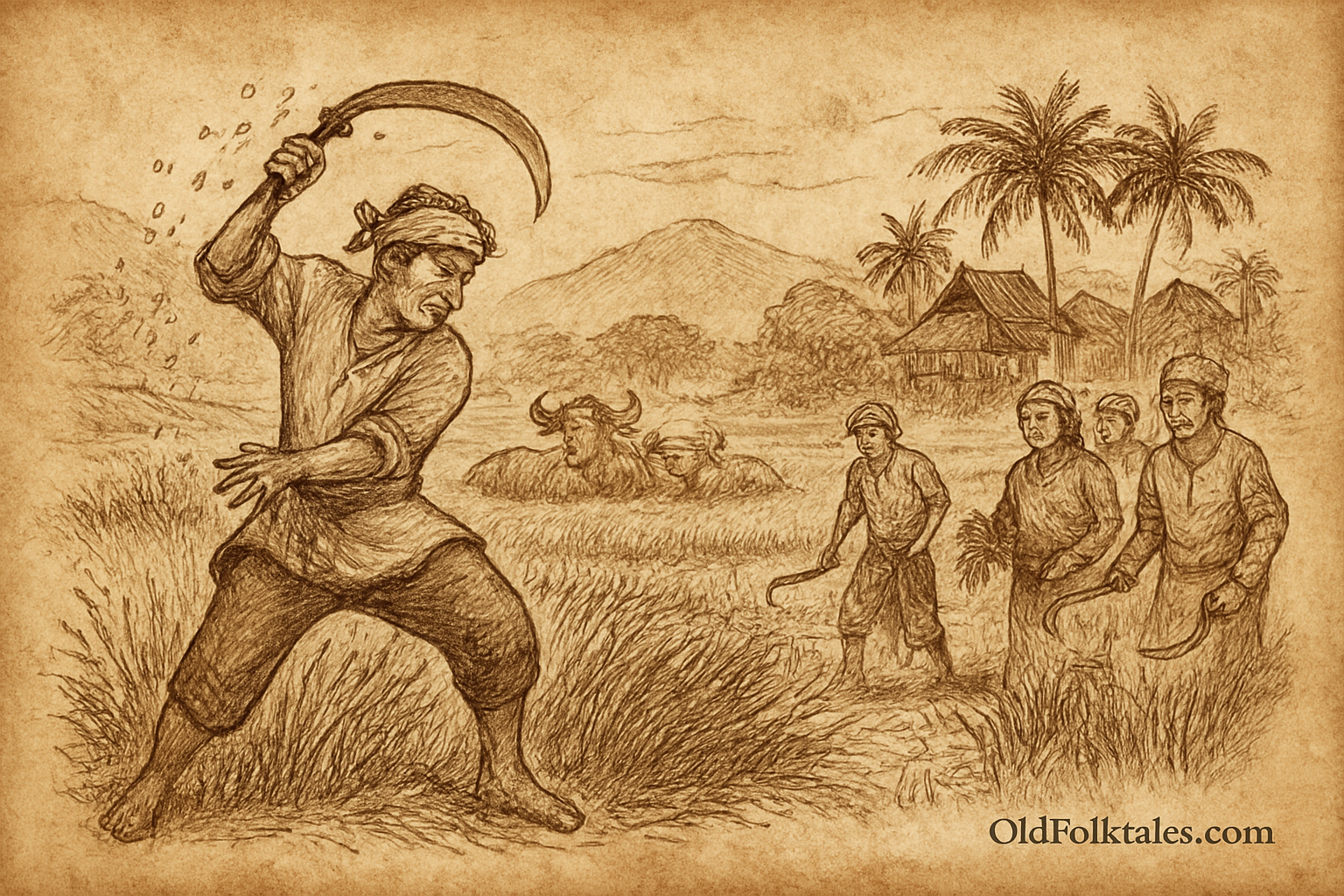

Instead of using a hand sickle and cutting each stalk carefully as tradition dictated, Si Paloian borrowed a large scythe, the kind used for cutting grass and wild vegetation. He reasoned that by using a bigger blade and making sweeping cuts, he could harvest his entire field in a fraction of the time it took his neighbors to harvest theirs.

The village elders, seeing his preparation, tried to warn him. “Si Paloian, padi must be harvested with care. The grain is delicate. If you use that scythe, you will lose much of your harvest.”

But Si Paloian waved away their concerns. “You are simply stuck in the old ways,” he said confidently. “Watch and learn from my superior method.”

He entered his field with the scythe and began making great sweeping cuts, expecting to see neat bundles of rice falling before him. Instead, disaster unfolded. The scythe’s blade was too coarse and its swing too violent. With each cut, rice grains scattered in every direction, knocked loose from their stalks by the force of the blow. The plants he had neglected to weed properly tangled with his tool, causing it to catch and tear rather than cut cleanly. The stalks that had suffered from inadequate water were brittle and shattered under the scythe’s impact, losing their grain entirely.

Within minutes, Si Paloian realized his mistake. The ground around him was littered with scattered rice grains, and his field looked like it had been ravaged by a storm rather than harvested. In his attempt to save time, he was losing most of his crop.

Panic set in. Si Paloian dropped the scythe and fell to his knees, trying desperately to gather the scattered grains by hand, but the task was impossible. Rice grains were everywhere, mixed with mud, scattered among stubble, impossible to collect efficiently. All his work for the entire growing season was being lost because of his impatience at harvest time.

His neighbors, working in the adjacent fields, heard his cries of distress and came to see what had happened. When they saw the disaster, they could have laughed at his foolishness or reminded him that they had warned him. Instead, without a word, they set down their own tools and came to help.

The village came together that afternoon in a display of communal cooperation that was at the heart of kampong life. Some helped Si Paloian carefully harvest what remained of his standing rice using proper techniques. Others painstakingly gathered scattered grains from the ground, salvaging what they could. Still others shared portions of their own harvests with him, ensuring that Si Paloian and his family would have enough rice to eat through the coming year.

As they worked, the elders gently explained what Si Paloian should have known all along. Rice cultivation, they told him, is not just about planting seeds and cutting stalks. It is about understanding the plant’s needs at each stage of growth, about being present and attentive throughout the season, about respecting methods developed over countless generations through trial and error.

“Our ancestors learned these techniques through hard experience,” one old farmer explained as he showed Si Paloian the proper way to use a hand sickle. “They tried many approaches and found what works best. When we follow the traditional methods, we honor their wisdom and we ensure good harvests.”

Another farmer, binding rescued rice stalks into proper bundles, added, “Rice farming requires patience, Si Paloian. You cannot rush a plant’s growth, and you cannot harvest carelessly what you have spent months cultivating. The shortcuts you seek do not exist in agriculture. The only path is the patient one.”

By the end of that long day, Si Paloian’s field had been harvested, though his yield was far smaller than it should have been. Without the help of his neighbors, he would have lost nearly everything. As they sat together sharing a simple meal in the gathering darkness, Si Paloian felt profound shame but also profound gratitude.

“I have been a fool,” he admitted, his voice heavy with genuine remorse. “I thought I was clever, but I was only arrogant. I dismissed the wisdom of our ancestors and the advice of my neighbors, and I nearly destroyed my entire harvest. You had every right to leave me to face the consequences of my foolishness, yet you helped me instead. Why?”

An elderly woman, who had led the effort to gather scattered grains, smiled at him with kindness. “Because we are a community, Si Paloian. When one person struggles, we all help, even when the struggle is of their own making. But we hope that you will learn from this experience. Cooperation is as important in farming as patience. We succeed together, not alone.”

The next growing season, Si Paloian was a changed farmer. He attended when the elders explained the proper timing for each agricultural task. He worked alongside his neighbors, learning from their experience rather than dismissing it. He tended his field with regular care, understanding now that this attention was not tedious but necessary. And when harvest time came, he used a proper hand sickle, cutting each stalk with care, grateful for every grain he collected.

His harvest that year was abundant, and Si Paloian made sure to share generously with those who had helped him in his time of need. He had learned that in rice farming, as in life, there are no real shortcuts, only the patient path of doing things properly, and that the community’s wisdom and support are treasures more valuable than any individual cleverness.

The story of Si Paloian and the padi field is still told in Bruneian kampongs today, often with laughter but also with affection. Si Paloian appears in many tales, and in each one, his clever but reckless nature leads him into trouble from which he must be rescued by the patience and cooperation of others. These stories serve as gentle reminders that traditional wisdom exists for good reasons, that patience is not the opposite of intelligence but rather its companion, and that community support is both a blessing to receive and a responsibility to give.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

This tale teaches that there are no genuine shortcuts in work that requires patient attention and traditional knowledge. Si Paloian’s attempt to harvest rice faster through improvised methods resulted in losing most of his crop, demonstrating that innovation without understanding leads to disaster. The story also celebrates communal cooperation, showing how communities thrive when members help one another even through self-inflicted troubles. True wisdom lies in respecting agricultural customs developed over generations and in valuing patience as the path to genuine success.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Si Paloian in Bruneian folklore? A: Si Paloian is a recurring trickster character in Bruneian folktales, portrayed as clever but reckless and impatient. He constantly seeks shortcuts and dismisses traditional methods, convinced his innovative approaches are superior to ancestral wisdom. His character appears in many stories where his impulsiveness leads to trouble, teaching lessons through his mistakes.

Q2: What mistakes did Si Paloian make during the growing season? A: Si Paloian neglected proper field maintenance throughout the growing season. He refused to pull weeds individually, ignored low water levels during dry spells, and didn’t protect his ripening grain from birds. While his neighbors tended their fields with regular care and attention, Si Paloian spent most of his time resting, assuming rice would grow well without constant monitoring.

Q3: What was Si Paloian’s disastrous harvesting method? A: Instead of using the traditional hand sickle to carefully cut each rice stalk, Si Paloian used a large scythe meant for cutting grass, believing he could harvest much faster. The violent sweeping cuts scattered rice grains everywhere, the coarse blade tangled with weeds he hadn’t removed, and brittle stalks from inadequate watering shattered on impact, causing him to lose most of his harvest.

Q4: How did the community respond to Si Paloian’s disaster? A: Rather than mocking Si Paloian or saying “I told you so,” his neighbors immediately set aside their own work to help him. They salvaged what remained of his standing rice using proper techniques, painstakingly gathered scattered grains from the ground, and even shared portions of their own harvests to ensure his family would have enough rice for the year.

Q5: What lessons did the elders teach Si Paloian while helping him? A: The elders explained that rice cultivation requires understanding the plant’s needs at each growth stage, being present and attentive throughout the season, and respecting methods developed over countless generations. They taught him that patience is essential, that shortcuts don’t exist in agriculture, and that traditional techniques embody ancestors’ wisdom earned through hard experience and trial and error.

Q6: What does this folktale reveal about traditional Bruneian rice farming culture? A: The story reflects the communal nature of kampong agricultural life, where farmers help one another and share knowledge across generations. It demonstrates the sophisticated understanding required for successful rice cultivation, the importance of following seasonal rhythms and proper techniques, and the cultural value placed on patience, cooperation, and respect for ancestral agricultural wisdom as foundations of community prosperity.

Source: Adapted from traditional Bruneian oral folklore

Cultural Origin: Kampong communities, Brunei Darussalam (traditional rice-farming culture)