In a village where houses stood on stilts above the marshy ground and cooking fires had burned warm for generations, there lived a family whose kitchen suddenly turned as cold as a mountain stream in winter. This was the household of Pak Ismail and Mak Zainab, respected members of the community who had raised five children and always kept a welcoming hearth. Their kitchen had been the heart of their home, filled with the aromas of sambal being ground, rice steaming in clay pots, and kuih frying in bubbling oil. Neighbors would often pause near their house, drawn by the warmth and delicious smells that spoke of love and abundance.

But one morning, everything changed.

Mak Zainab woke before dawn as she always did, ready to prepare the family’s first meal. She arranged the kindling in the traditional stone hearth, struck the flint, and watched the flames catch and grow. The fire burned as brightly as ever, its orange glow dancing across the wooden walls, but something was terribly wrong. No heat radiated from the flames. The air around the fire remained as cold as if the hearth were filled with ice rather than burning wood.

Confused and disturbed, Mak Zainab called her husband. Pak Ismail came quickly, his brow furrowed with concern. He placed his hand near the flames and jerked it back, not from heat but from the shocking coldness that emanated from the fire itself. The flames looked normal, flickered normally, consumed the wood normally, yet they gave no warmth whatsoever.

“This is not natural,” Pak Ismail muttered, his voice tight with worry. “Fire that does not warm is fire that has been cursed.”

They tried building a larger fire, using different wood, relocating the hearth to another spot in the kitchen. Nothing worked. The flames burned bright but cold, and the kitchen remained as frigid as a cave deep underground. When Mak Zainab tried to cook rice, the water in the pot refused to boil despite sitting directly over the flames. When she attempted to fry banana fritters, the oil remained cool and the batter simply soaked into it, becoming soggy and inedible.

The family’s youngest daughter, Siti, began to cry from the cold. The older children huddled together, their breath visible in the air despite the roaring fire. Pak Ismail and Mak Zainab exchanged frightened glances. Whatever had befallen their kitchen was beyond ordinary understanding.

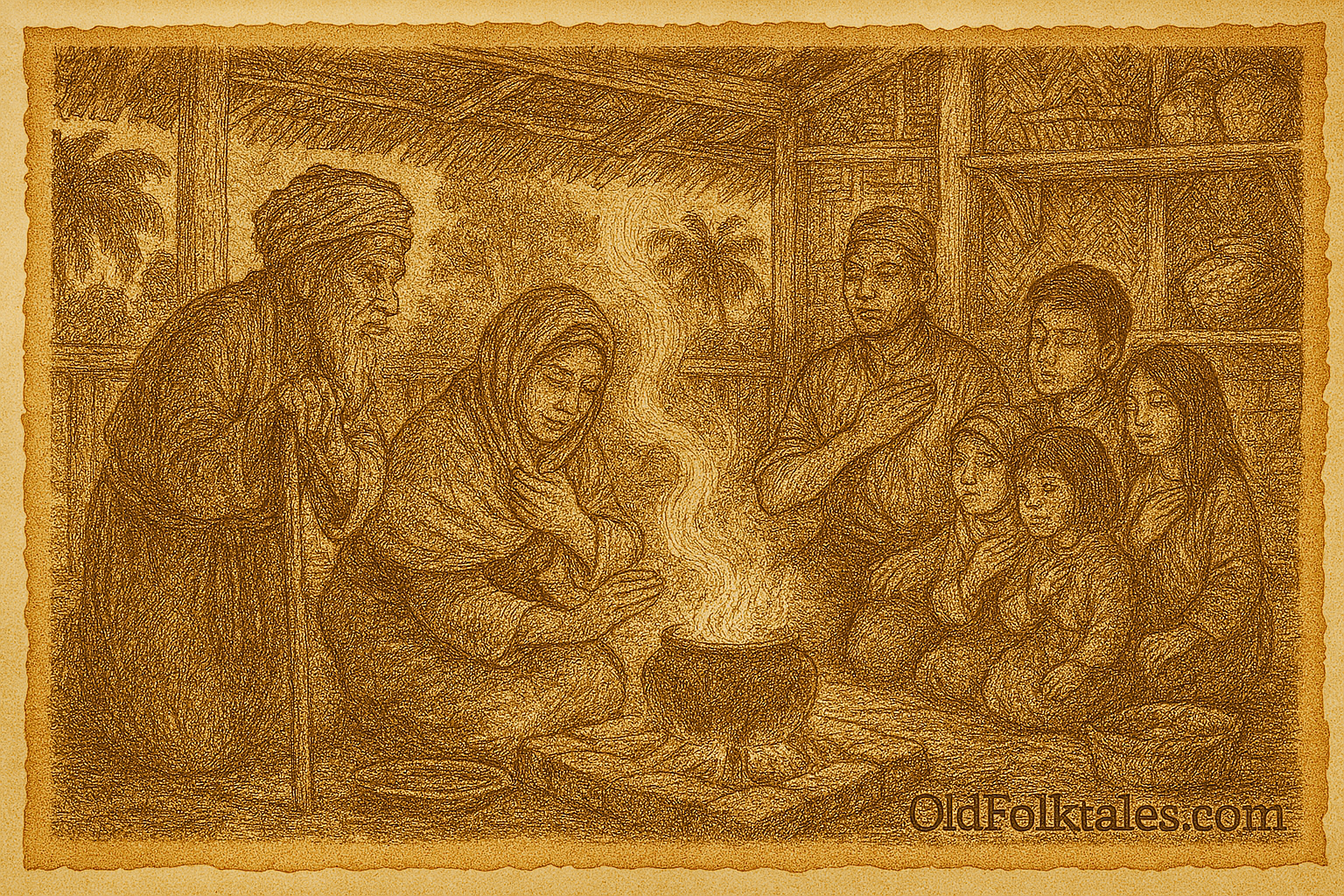

News of the cold kitchen spread quickly through the village. Neighbors came to witness the impossible sight: flames that looked like fire but felt like ice, a kitchen that should have been the warmest room in the house but instead seemed colder than the night air outside. Some whispered that it was black magic, others suggested a demon had taken residence, but most agreed that this was a matter requiring the wisdom of the elders.

Tok Ayah, the oldest man in the village and keeper of traditional knowledge, was summoned. He arrived leaning heavily on his walking stick, his eyes sharp despite his advanced years. He had seen many strange things in his long life and understood that the visible world was only a thin curtain over the realm of spirits and forces that most people never perceived.

Tok Ayah stood in the doorway of the cold kitchen for a long time, not entering, simply observing. He watched how the smoke rose from the fire, noted the way the shadows fell, listened to sounds that others couldn’t hear. Finally, he turned to Pak Ismail and Mak Zainab, his expression grave.

“Tell me,” he said slowly, “have there been any changes in this household recently? Any departures from the old ways? Any disrespect shown to the traditions that govern domestic life?”

Pak Ismail and Mak Zainab looked at each other, uncertainty in their eyes. They were good people, faithful and respectful. What could they have done to deserve this punishment?

“We have done nothing wrong,” Pak Ismail insisted. “We live as our parents taught us, we honor the traditions, we make our offerings at the proper times.”

But Tok Ayah shook his head slowly. “The kitchen spirit does not grow cold without reason. Something has been done or left undone. Think carefully.”

It was then that Mak Zainab’s face paled as a memory surfaced. Three weeks earlier, during the chaos of preparing for her eldest son’s wedding, she had been so busy that she had forgotten to perform the monthly kitchen blessing. This was an old ritual, one passed down through generations of women, where offerings of rice and flowers were placed at the hearth’s corner to honor the kitchen guardian spirit. In her exhaustion and distraction, she had simply forgotten.

Worse, she remembered now how she had snapped at her daughter for making a mess while cooking, scolding her harshly right at the hearth itself. The old people always said that angry words spoken at the cooking fire would offend the spirit that dwelled there, yet in her frustration, Mak Zainab had forgotten this taboo.

And there was more. Her teenage son, influenced by modern ideas from the town, had begun mocking the old customs. He had laughed at his grandmother’s insistence on certain kitchen protocols, had deliberately broken small rules to prove they were “just superstition,” and had even kicked at the corner where offerings were traditionally placed, declaring it a waste of space.

As Mak Zainab confessed these violations, tears streaming down her face, Tok Ayah nodded gravely.

“The kitchen is sacred ground,” he explained to the family gathered in the cold room. “It is where life is sustained, where raw becomes cooked, where nature’s gifts are transformed into nourishment. The kitchen spirit, whom we call the Penunggu Dapur, guards this transformation. When we show disrespect through forgotten rituals, harsh words, or mockery of tradition, we break the harmony that allows the spirit to bless our hearth with warmth and abundance.”

“What can we do?” Pak Ismail asked desperately. “How do we restore what has been lost?”

Tok Ayah was silent for a moment, then spoke. “The spirit must be appeased. You must perform the ritual of apology and restoration. It will require seven days of careful observance and sincere repentance.”

He instructed them in the necessary steps. For seven days, no harsh words could be spoken anywhere in the house. The family must eat only cold food during this time, sharing in the discomfort their disrespect had caused. Each dawn and dusk, Mak Zainab must place offerings of white rice, yellow flowers, and incense at the hearth’s corner, speaking words of apology and respect. The son who had mocked the traditions must personally clean every surface of the kitchen with water mixed with special herbs, asking forgiveness with each stroke.

Most importantly, the entire family must gather each evening by the cold hearth and speak aloud their gratitude for every meal the kitchen had ever provided, every moment of warmth it had given, every blessing it had brought to their lives.

The family committed themselves to this difficult task. The first days were hardest. Eating cold rice and uncooked vegetables while the useless fire burned its cold flames was a constant reminder of what they had lost. The son who had been so skeptical found himself weeping as he scrubbed the kitchen walls, finally understanding the weight of what he had dismissed as superstition. Mak Zainab’s offerings were made with genuine remorse, her voice breaking as she apologized to the unseen spirit she had neglected.

On the seventh evening, as the family gathered for their final prayer of gratitude, something extraordinary happened. As they spoke their thanks, the fire in the hearth began to flicker differently. The flames, which had burned cold and lifeless for days, suddenly pulsed with a warm, golden light. Heat, blessed and natural, began to radiate from the fire.

Little Siti noticed it first. “Mama,” she whispered, “I can feel it. The fire is warm again!”

Indeed, the cold that had gripped the kitchen for a week was melting away like morning mist before the sun. The air grew pleasant, then comfortable, then genuinely warm. Mak Zainab rushed to place a pot of water over the flames, and within minutes, it was bubbling and steaming as it should.

The family wept with relief and joy. Tok Ayah, who had come to observe the final ritual, smiled with satisfaction.

“Remember this always,” he told them. “The home is a sacred space, and the kitchen is its heart. The warmth of your hearth depends not just on wood and fire, but on respect, gratitude, and harmony. Traditions are not empty customs but the accumulated wisdom of generations. They maintain the balance between our world and the realm of spirits. Honor them, and you will be blessed. Neglect them, and you may find that even fire cannot warm you.”

From that day forward, Pak Ismail’s household never again forgot the kitchen rituals. The monthly offerings were made with care, harsh words at the hearth were avoided, and the traditions were taught to each new generation with proper reverence. The kitchen remained warm and welcoming, a place of nourishment and blessing, and the story of the cold fire was told and retold as a reminder of the unseen forces that share our homes and the respect they require.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

The legend of Celap Dapur teaches us that domestic harmony extends beyond human relationships to include respect for the spiritual forces that inhabit our living spaces. Traditional household rituals and taboos are not mere superstitions but represent accumulated wisdom about maintaining balance between the physical and spiritual realms. When we neglect these practices or show disrespect through harsh words, mockery, or forgotten obligations, we disrupt the harmony that brings blessing and comfort to our homes. The story emphasizes that restoration requires genuine repentance, shared sacrifice, and renewed commitment to respectful behavior. Most importantly, it reminds us that the warmth and abundance of a household depend as much on spiritual respect and gratitude as on physical resources.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What happens to Pak Ismail and Mak Zainab’s kitchen in this Malaysian folk tale? A: Their kitchen becomes supernaturally cold despite having normal burning fires. The flames look and burn normally but give off no heat, making it impossible to cook food or warm the space. This impossible coldness represents the withdrawal of spiritual blessing from the household due to broken taboos and disrespectful behavior toward traditional kitchen customs.

Q2: Who is the Penunggu Dapur in Malaysian folklore? A: The Penunggu Dapur is the kitchen guardian spirit that protects the hearth and blesses it with warmth and the ability to transform raw food into nourishment. This spirit represents the sacred nature of the kitchen space and requires respect through proper rituals, offerings, and behavior. When offended, the spirit withdraws its blessing, causing supernatural problems like the cold fire.

Q3: What taboos and disrespectful actions caused the kitchen to become cold? A: The family violated several sacred rules including forgetting the monthly kitchen blessing ritual, speaking harsh and angry words at the hearth, and allowing a family member to mock traditional customs and deliberately break kitchen protocols. These accumulated disrespects offended the kitchen spirit and broke the harmony necessary for the hearth to function properly with spiritual blessing.

Q4: Who is Tok Ayah and what is his role in the story? A: Tok Ayah is the village elder and keeper of traditional knowledge who understands the spiritual dimensions of daily life. He serves as the intermediary who can diagnose spiritual problems and prescribe the proper rituals for restoration. His character represents the importance of preserving traditional wisdom and respecting elders who understand the delicate balance between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Q5: What rituals must the family perform to restore warmth to their kitchen? A: The family must observe seven days of careful ritual including speaking no harsh words anywhere in the house, eating only cold food to share in the discomfort caused by their disrespect, placing daily offerings of white rice, yellow flowers and incense at the hearth, having the offending son clean the kitchen while asking forgiveness, and gathering each evening to speak gratitude for past blessings. This collective repentance and sacrifice restores spiritual harmony.

Q6: What does this story teach about traditional Malaysian household beliefs? A: This story teaches that in traditional Malaysian culture, the home (especially the kitchen) is viewed as a sacred space inhabited by guardian spirits that must be honored through proper rituals and respectful behavior. Domestic harmony depends on maintaining balance between physical and spiritual realms through observance of taboos, regular offerings, and avoiding negative speech or actions in sacred spaces. The tale emphasizes that modern skepticism toward these traditions can have real consequences and that accumulated wisdom should be respected rather than dismissed.

Cultural Origin: Malaysia, Southeast Asia.