In a village nestled deep within the Malaysian jungle, where ancient trees towered overhead like cathedral pillars and the calls of gibbons echoed through morning mist, there lived a young man whose modern education had filled his head with skepticism. The villagers knew him simply as Si Pemuda, the Youth and he had become notorious for his dismissive attitude toward the traditional beliefs that had guided his community for countless generations.

The village itself was a place where old ways still held power. Wooden houses with steep roofs stood elevated on sturdy posts, their walls adorned with intricate carvings that told stories of ancestors and spirits. The elders gathered each evening beneath the community hall to share wisdom and remind the younger generation of the pantang the sacred taboos and prohibitions that protected them from harm. These were not mere superstitions but accumulated knowledge, lessons written in the blood and bones of their forebears.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

Among the most important pantang was the prohibition against entering certain areas of the surrounding forest. The elders spoke of the hutan larangan the forbidden forest with hushed voices and serious expressions. These were places where the boundary between the human world and the realm of spirits grew dangerously thin, where unseen forces dwelled and ancient laws governed. Massive trees marked the boundaries, their trunks wrapped with yellow cloth and offerings of flowers and rice left at their roots as signs of respect.

“Do not enter the forbidden groves,” the elders warned repeatedly. “Do not venture past the marked trees when the sun begins to set. Do not call out loudly in certain clearings, for you may attract attention you do not want. These rules were not created to restrict you but to protect you.”

Si Pemuda would listen to these warnings with barely concealed contempt. He had attended school in the city, where teachers spoke of science and reason, where forests were just collections of trees and animals, where spirits belonged only in storybooks for children. He saw the pantang as relics of ignorant times, obstacles to progress, chains that bound his people to irrational fear.

“These are just superstitions,” he would say loudly, his voice dripping with disdain. “There are no spirits in the forest only trees and animals. The forbidden areas are no different from any other part of the jungle. You’re all prisoners of old wives’ tales and baseless fears.”

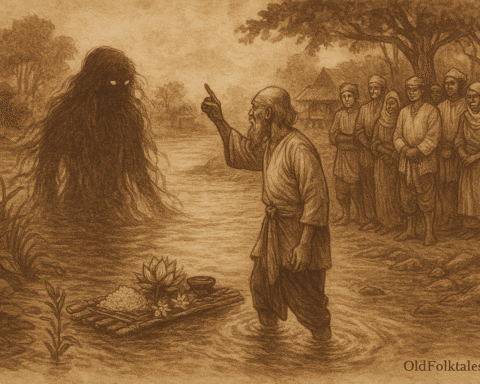

The elders would shake their heads sadly, recognizing the dangerous pride in his words. They had seen this before young people who thought themselves wiser than their ancestors, who believed that education in distant cities made them superior to generations of accumulated knowledge. They tried to warn him, to explain that the pantang existed because others before him had suffered for ignoring them, but Si Pemuda refused to listen.

His mother would plead with him. “Please, anak, do not speak this way. Do not tempt fate. The forest is old, older than our village, older than our memories. There are things we do not understand but must respect.”

His grandmother, her face creased with age and wisdom, would grip his hand with surprising strength. “Boy, I have lived long enough to see what happens to those who mock the pantang. Listen to those who love you. Some knowledge cannot be learned from books, it must be earned through humility.”

But their words fell on deaf ears. Si Pemuda’s arrogance had grown too large, fed by his education and the admiration of other young people who saw him as progressive and fearless. He began to openly challenge the taboos, deliberately breaking minor prohibitions to prove they held no power.

Then came the day when his skepticism led him to commit the ultimate transgression.

It was late afternoon when Si Pemuda announced his intention to enter the deepest part of the hutan larangan, the area most strictly forbidden. A group of younger villagers had gathered around him, some encouraging his bravado, others uncomfortable but unwilling to seem as fearful as their elders. The sun was already beginning its descent toward the horizon, casting long shadows through the jungle canopy.

“I’ll prove there’s nothing to fear,” Si Pemuda declared loudly, his voice echoing off the trees. “I’ll walk through the forbidden forest and return unharmed. Then perhaps everyone will finally abandon these ridiculous superstitions and join the modern world.”

The elders tried once more to stop him, but he brushed past them with a contemptuous laugh. He strode toward the boundary markers the great trees wrapped in yellow cloth and without pausing or showing any respect, he stepped across the threshold into the forbidden territory.

The forest seemed to swallow him immediately. The other young people watched as he disappeared between the massive tree trunks, his confident figure growing smaller and then vanishing entirely into the green shadows. They waited at the boundary, expecting him to emerge within an hour, triumphant and vindicated.

But an hour passed, then another. The sun sank lower, painting the sky orange and red. Darkness began creeping through the jungle like a living thing. The young people grew nervous and eventually scattered home, leaving only Si Pemuda’s family keeping vigil at the forest’s edge.

Inside the forbidden territory, Si Pemuda’s confidence had begun to erode almost immediately. The forest here felt different oppressively quiet despite the normal sounds of insects and birds. The trees seemed larger, older, their twisted roots creating a maze that confused his sense of direction. He told himself it was just his imagination, just the dimming light playing tricks, but an uncomfortable prickling sensation crawled up his spine.

He tried to retrace his steps, but the paths looked unfamiliar. Every tree appeared identical, every direction equally uncertain. The confident mental map he’d had of the forest’s layout seemed to have dissolved. He walked faster, then broke into a run, branches whipping at his face, thorns catching his clothes.

As darkness fell completely, the true horror began. Strange lights flickered between the trees not fireflies but something else, something that moved with purpose and seemed to watch him. Sounds echoed through the forest that resembled human voices but were subtly wrong, as if something inhuman was trying to mimic human speech. Laughter rippled through the darkness, coming from all directions at once.

Si Pemuda ran blindly, terror replacing his earlier arrogance. He tripped over roots, crashed through undergrowth, called out for help until his voice grew hoarse. But the forest seemed to twist around him, paths leading him in circles, familiar landmarks appearing and disappearing impossibly. Time lost meaning in the darkness. Hours felt like days, minutes stretched into eternities.

He saw things he could not explain shadows that moved independent of any light source, trees that seemed to shift position when he wasn’t looking directly at them, a figure that stood motionless in the distance, watching him with eyes that gleamed in the darkness. Hunger gnawed at his stomach, thirst parched his throat, but he dared not eat any fruit or drink from any stream, some survival instinct warning him that nothing in this place was safe.

On the third day or was it the fourth? He had lost count Si Pemuda collapsed at the base of an enormous tree, too exhausted to continue. His fine clothes were torn to rags, his skin covered in scratches and insect bites, his feet bleeding and swollen. The arrogance that had driven him into this place had been completely stripped away, replaced by a desperate terror and a profound understanding of how small and powerless he truly was.

“Please,” he whispered to the forest, to whatever forces dwelled within it, tears streaming down his face. “I’m sorry. I was wrong. I should have listened. I should have respected the pantang. Please, let me go home. Let me see my family again.”

His plea hung in the air, carried away by a breeze that seemed to rise from nowhere. The oppressive atmosphere lightened slightly, as if something had been listening and had finally heard genuine remorse in his voice.

When dawn broke on the fifth day, search parties finally found him lying unconscious just beyond the boundary markers, as if the forest had deposited him there during the night. His family wept with relief, though the Si Pemuda they carried home was not the same confident young man who had entered the forbidden territory.

For days, he lay in his bed, feverish and delirious, speaking of things he had seen that made no sense. When he finally recovered enough to speak coherently, he was a changed person. The skepticism had been burned away, replaced by a profound humility and a deep respect for the wisdom of his ancestors.

He never again spoke dismissively of the pantang. Instead, he became one of the most vocal advocates for respecting the traditional prohibitions, warning other young people against the arrogance that had nearly cost him his life. He would describe his experience in the forbidden forest the disorientation, the terror, the sense of being lost not just physically but spiritually and his voice would shake with remembered fear.

“I thought education made me wise,” he would say to anyone who would listen, his eyes haunted by memories. “But I was a fool. Our elders’ warnings come from real knowledge, real experience. The pantang exist because others learned these lessons at great cost. We ignore them at our peril.”

The village elders welcomed his transformation, though they took no pleasure in the suffering that had caused it. They had seen this pattern before pride leading to punishment, punishment leading to wisdom. Some lessons, they knew, could only be learned through direct experience, no matter how many warnings were given.

Si Pemuda never ventured near the forbidden forest again. He would pass by the boundary markers wrapped in yellow cloth and bow his head respectfully, remembering the days and nights he had been lost, remembering the terror, remembering how close he had come to never returning at all.

And when his own children were old enough to understand, he made sure they learned the pantang, made sure they understood that respect for ancestral wisdom was not weakness but strength, not ignorance but the deepest kind of knowledge the knowledge that some boundaries exist for very real reasons, even when we cannot fully understand them.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

This tale teaches us that ancestral wisdom and cultural taboos are not arbitrary superstitions but accumulated knowledge earned through generations of experience. Si Pemuda’s arrogance believing his modern education made him superior to traditional knowledge led him into genuine danger that could have cost him his life. The story emphasizes that true wisdom requires humility and the recognition that our ancestors’ warnings carry weight earned through real suffering and observation. The pantang exist not to restrict freedom but to protect communities from dangers that may be spiritual, psychological, or environmental in nature.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What does “pantang” mean in Malaysian culture?

A: Pantang refers to sacred taboos, prohibitions, and traditional rules passed down through generations in Malaysian and Malay culture. These are not mere superstitions but accumulated wisdom meant to protect communities from spiritual, physical, or social harm. They represent ancestral knowledge about boundaries that should not be crossed.

Q2: Why was Si Pemuda skeptical of the village taboos?

A: Si Pemuda had received modern education in the city, which made him believe that science and reason had replaced the need for traditional beliefs. He viewed the pantang as outdated superstitions from ignorant times and considered himself more enlightened than his village elders, leading to dangerous arrogance.

Q3: What is the “hutan larangan” or forbidden forest in the story?

A: The hutan larangan (forbidden forest) refers to sacred areas of the jungle where the boundary between the human world and spirit realm is believed to be thin. These areas are marked with yellow cloth on trees and are strictly prohibited by village taboos due to spiritual dangers that dwell there.

Q4: What happened to Si Pemuda when he entered the forbidden forest?

A: He became completely lost and disoriented despite his confidence. He experienced supernatural phenomena including strange lights, inhuman voices, moving shadows, and illusions that kept him trapped for days. He suffered physical and psychological torment until he finally showed genuine remorse and respect for the forces he had mocked.

Q5: How did Si Pemuda change after his experience?

A: He was completely transformed from a skeptical, arrogant youth into a humble advocate for respecting traditional wisdom. He openly acknowledged his foolishness, warned others against similar pride, and became one of the strongest voices for honoring the pantang and ancestral knowledge.

Q6: What cultural lesson does this Malaysian folktale teach about tradition and modernity?

A: The story teaches that modern education and traditional wisdom are not mutually exclusive, and that dismissing ancestral knowledge as superstition is dangerous arrogance. True wisdom requires humility and recognition that generations of experience have value. Cultural taboos exist for real reasons, and respecting them is not ignorance but prudence and respect for accumulated knowledge.

Cultural Origin: Malaysian folklore, Malay Peninsula, Southeast Asia