In a remote village on the edge of Burma’s vast teak forests, where morning mist clung to the valleys like cotton and the calls of gibbons echoed through ancient trees, there lived a boy who had never seen the sunrise paint the sky gold, never watched birds take flight, never gazed upon his own mother’s face. He had been born without sight, his eyes open but unseeing, windows to a world that remained forever dark.

The boy’s parents loved him deeply, but their love was tinged with profound sorrow. In their village, where everyone contributed to survival through farming, weaving, or craftsmanship, they worried constantly about their son’s future. How would he work? How would he support himself when they were gone? How could he navigate a world built for those who could see?

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

As the boy grew from infant to child, he became acutely aware of his difference. He heard the other children running and playing games he could not join. He listened to them describe the brilliant colors of flowers, the shapes of clouds, the faces of loved ones all things that remained incomprehensible to him, abstract concepts without any frame of reference. He felt their pity in their careful voices, sensed their discomfort in their hesitant movements around him.

The darkness that surrounded him was not the worst of his burden. Far heavier was the weight of feeling useless, of being viewed as helpless, of sensing that others saw him not as a complete person but as a problem to be managed, a mouth to feed who could offer nothing in return.

By the time he reached his tenth year, despair had settled over the boy like a heavy blanket. He spent his days sitting outside his family’s bamboo house, listening to village life flow around him while feeling utterly separate from it. His hands remained idle while others worked. His feet stayed rooted while others moved with purpose. He began to wonder if his existence had any meaning at all, if perhaps the world would be better served if he had never been born.

His mother noticed the growing darkness in her son’s spirit a darkness far more concerning than his sightless eyes. She watched him withdraw further each day, speaking less, eating less, retreating into a place where even her love could not reach him. In her desperation, she remembered stories she had heard of a wise monk who lived in a small monastery deep in the forest, a man renowned for his insight into the human heart and his ability to see truth where others saw only surface appearances.

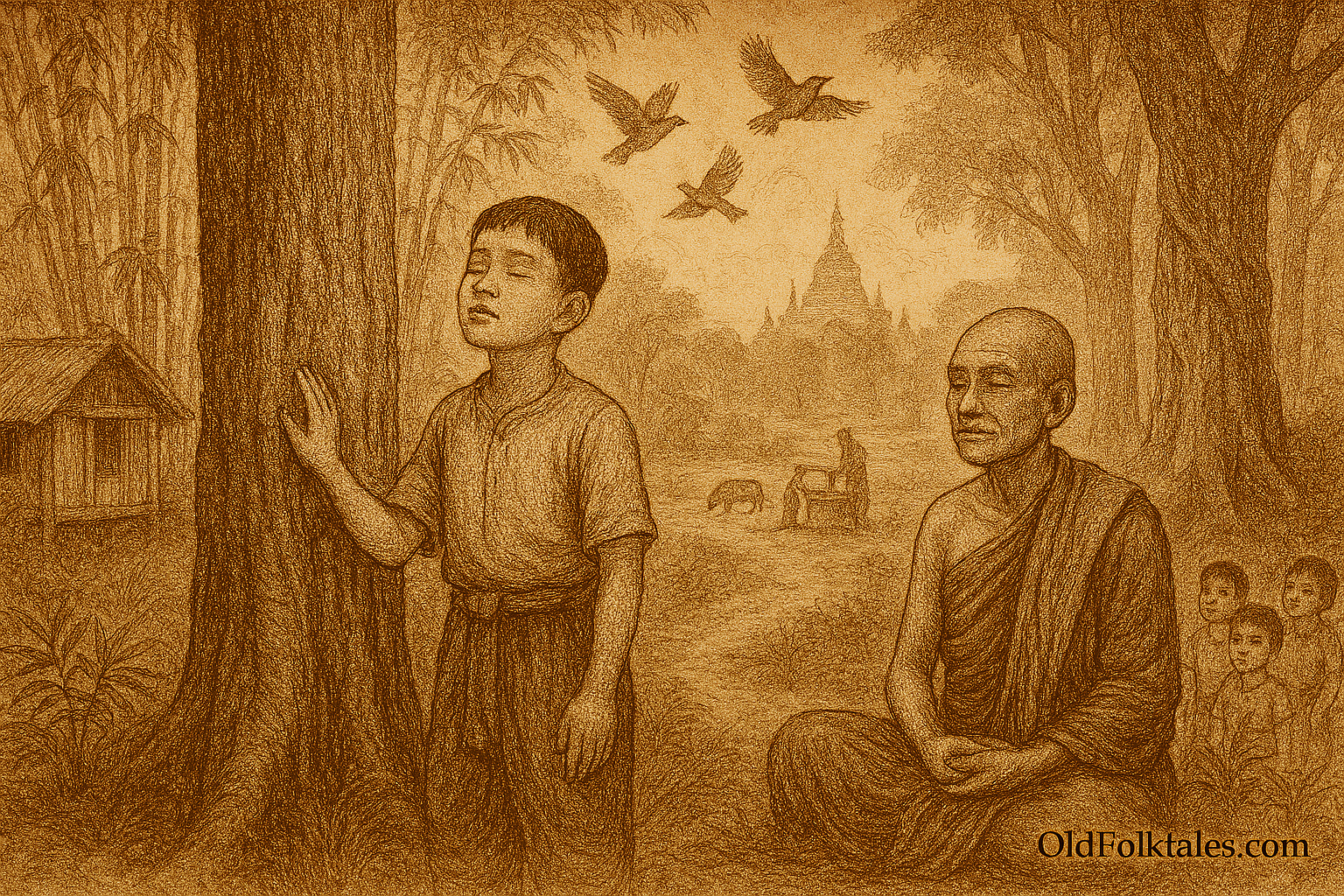

One morning, she guided her son through the forest paths to the monastery. The journey took several hours, the boy stumbling over roots and stones despite his mother’s careful guidance, each fall reinforcing his sense of helplessness. When they finally arrived at the simple wooden structure where the monk lived, the boy was exhausted, bruised, and more convinced than ever of his own worthlessness.

The monk was ancient, his face creased with countless wrinkles that mapped a long life of contemplation and wisdom. When the mother explained her son’s despair, the monk nodded slowly, his expression thoughtful. He asked the mother to leave the boy with him for one month, promising to care for him and perhaps offer him a different perspective on his condition.

The mother hesitated, torn between hope and fear, but something in the monk’s calm certainty made her trust him. She kissed her son’s forehead and departed, leaving him in the care of this stranger.

For the first three days, the monk said nothing to the boy about his blindness. He simply included him in the daily routines of monastic life rising before dawn, performing simple cleaning tasks, preparing rice, sitting in meditation. The boy fumbled through these activities, frustrated and embarrassed by his constant mistakes, but the monk never showed impatience or pity. He simply guided the boy’s hands when necessary and otherwise let him struggle and learn.

On the fourth day, as they sat together after the morning meal, the monk finally spoke directly about the boy’s condition.

“Tell me, child, what does it mean to truly see?”

The boy felt a familiar surge of bitterness. “I wouldn’t know. I’ve never seen anything.”

“Haven’t you?” the monk replied calmly. “Close your eyes.”

“They’re always closed,” the boy said sharply. “That’s the problem.”

“No,” the monk corrected gently. “Your eyelids may be open, but you have closed yourself off from the world in other ways. Now, please, humor an old man. Take a deep breath and tell me what you perceive.”

Reluctantly, the boy complied. He breathed in deeply through his nose and was surprised to find himself noticing things he had been too wrapped in self-pity to acknowledge. “I smell jasmine,” he said slowly. “And sandalwood incense. And something cooking is that ginger?”

“Good,” the monk encouraged. “What else?”

The boy focused his attention on his other senses. “I hear birds many different kinds. Some chirp, some whistle, some make clicking sounds. I hear wind moving through bamboo, which sounds different from wind through teak leaves. I hear a stream somewhere nearby, flowing over rocks.”

“Excellent. And what do you feel?”

“The sun is warm on my left side but not my right, so I’m sitting in partial shade. The ground beneath me slopes slightly downward toward my front. There’s a breeze coming from the direction of the stream, cooler than the air around us.”

The boy paused, surprised by how much information he had gathered without sight. The monk’s gentle voice continued: “You just demonstrated something that most people with sight fail to understand vision is only one way of perceiving the world, and often not the most reliable. Those who rely too heavily on their eyes miss the subtle truths that other senses reveal.”

Over the following weeks, the monk trained the boy systematically in the art of awareness. Each day brought new exercises designed to sharpen his remaining senses and teach him to navigate the world through sound, touch, smell, and intuition.

The monk taught him to identify different trees by the texture of their bark, the shape of their leaves, the sound wind made passing through their branches. The boy learned that teak had smooth bark that felt cool even in sunlight, while the bark of wild mango was rough and retained heat. He discovered that bamboo creaked when wind moved through it, creating an almost musical sound quite different from the rustling of broader leaves.

He learned to navigate by sound, understanding that open spaces carried echoes differently from enclosed ones, that water flowing over stones created specific patterns of sound that revealed the stream’s depth and speed, that the calls of certain birds indicated the time of day as reliably as any sundial.

The monk taught him to feel changes in air pressure and temperature that signaled approaching weather. The boy discovered he could sense rain coming hours before it fell by the way humidity increased and pressure dropped, by how certain smells intensified and birds changed their behavior.

Most importantly, the monk taught him to develop what he called “listening beyond hearing” a form of intuition that combined all his senses with careful attention to patterns and subtle cues. The boy learned to sense when someone approached before hearing their footsteps, to know whether a path ahead was clear or blocked without physical contact, to feel the presence of obstacles through changes in how sound and air moved around him.

As the weeks passed, something remarkable happened. The boy’s posture changed he stood straighter, moved with growing confidence. His face, which had been downcast and closed, began to open with curiosity and engagement. He smiled for the first time in years when he successfully identified a bird species by its call alone, when he navigated a forest path without stumbling, when he sensed a snake crossing the trail and avoided it before the monk could warn him.

“You are beginning to see,” the monk told him one evening as they sat together listening to the forest settle into dusk. “Not with your eyes, but with your whole being. This is a form of vision that sighted people rarely develop because they never have to. It is, in many ways, more reliable than physical sight, which can be deceived by shadows, distance, and expectation.”

When the month ended and the boy’s mother returned to collect him, she barely recognized her son. He walked beside the monk with confidence, his head raised, his movements fluid and assured. When she called his name, he turned immediately toward her voice and moved in her direction without hesitation, navigating around obstacles she hadn’t even mentioned.

“What has happened?” she asked in wonder. “He seems transformed.”

The monk smiled. “Your son has learned to see. Not despite his blindness, but in some ways because of it. He has developed abilities that most people never cultivate because they rely solely on their eyes. He is ready now to find his purpose in the world.”

The boy returned home, but he was no longer the despairing child who had left. He began to explore the forest surrounding his village, memorizing paths through his enhanced senses, understanding the terrain in ways that went beyond visual landmarks. He learned to read the forest like others read books understanding its moods, its dangers, its hidden gifts.

Word of his abilities spread gradually through the region. Travelers passing through the area would sometimes get lost in the dense forest, especially during fog or darkness. Villagers who went searching for them would often fail, their eyes useless in the gloom, their sense of direction confused by the maze of similar-looking trees.

But the blind boy could navigate the forest in any condition. Darkness meant nothing to him he had lived in it his entire life. Fog that blinded others did not affect his perception. He could track lost travelers by the faint sounds of their movement, the disturbance they left in vegetation, the changes they created in the forest’s natural patterns.

The first time villagers asked for his help finding a lost merchant, many were skeptical. How could a blind child succeed where sighted adults had failed? But the boy simply smiled and set off into the forest. Within two hours, he returned with the terrified merchant, who had been wandering in circles mere miles from the village but completely disoriented in the thick morning fog.

From that day forward, the blind boy became known as the village’s most reliable guide. Merchants traveling through the region would specifically seek him out to lead them through difficult passages. During the rainy season when paths became treacherous and visibility poor, only the boy could safely guide people through the forest.

He never saw the gratitude in the eyes of those he helped, never observed the respect in the bows they gave him, never viewed the coins they pressed into his hands as payment. But he felt all of it through their voices, their touch, the energy of their presence. And he knew, with a certainty that went deeper than vision, that his life had meaning, that his existence was not a burden but a gift both to himself and to others.

Years later, when travelers would ask how a blind boy had become the forest’s greatest guide, the villagers would repeat the words he had learned from the monk: “True sight comes not from the eyes but from understanding. The boy sees more than any of us, not despite his blindness, but because of what it taught him to develop. He perceives the world as it truly is, not as it merely appears to be.”

And the boy, now a respected young man, would smile when he heard these words, remembering the darkness of his despair and the light of understanding that had replaced it a light that needed no eyes to perceive, no vision to illuminate the path forward.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

This Burmese folktale teaches that physical limitations need not define our worth or limit our potential. True sight comes from understanding and awareness, not merely from physical vision. The boy’s blindness, initially viewed as a tragic disability, became the foundation for developing extraordinary abilities that served his community in ways sighted people could not match. The story emphasizes that challenges can become gifts when we learn to develop our other strengths, and that purpose in life comes not from conforming to others’ expectations but from discovering and cultivating our unique capabilities.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What was the blind boy’s main struggle at the beginning of the story?

A: Beyond his physical blindness, the boy struggled with feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness. He believed he could contribute nothing to his village, felt separated from normal life, and sank into despair thinking his existence was meaningless. His spiritual darkness was more debilitating than his lack of physical sight.

Q2: What did the wise monk teach the boy during their month together?

A: The monk taught the boy to develop his other senses systematically identifying trees by bark texture and sound, navigating by acoustic patterns, sensing weather changes through temperature and pressure, and developing intuition by combining all sensory information. He learned that vision is only one form of perception and often not the most reliable.

Q3: How did the boy’s perception of his blindness change?

A: The boy transformed from viewing his blindness as a tragic limitation to understanding it as the foundation for developing extraordinary abilities. He realized that his lack of sight had forced him to develop sensory awareness and navigational skills that sighted people rarely cultivate, making him uniquely capable rather than disabled.

Q4: Why did the blind boy become the village’s most trusted guide?

A: The boy could navigate the forest in conditions where sight became useless or unreliable, such as thick fog, darkness, or heavy rain. His enhanced hearing, touch, and intuition allowed him to track lost people, sense obstacles, and find paths when visual landmarks disappeared. His blindness had trained him to perceive what others could not.

Q5: What does “true sight” mean in the context of this story?

A: True sight refers to deep understanding and awareness achieved through multiple forms of perception, not just visual observation. It means perceiving reality as it truly is rather than as it merely appears, combining sensory information with intuition and careful attention to patterns and subtle cues that eyes alone cannot detect.

Q6: What cultural and spiritual values does this Burmese tale reflect?

A: The story reflects Buddhist values of mindfulness, awareness, and the understanding that suffering can lead to enlightenment. It emphasizes the importance of looking beyond surface appearances, developing inner wisdom, and recognizing that conventional definitions of disability or ability often miss deeper truths about human potential and worth.

Source: Adapted from Folklore and Fairy Tales from Burma, a collection preserving the wisdom tales and moral teachings from Myanmar’s Buddhist cultural tradition.

Cultural Origin: Burmese folklore, Myanmar (Burma), Southeast Asia