In the vast deserts of the Jordanian Badia, where tribes like Bani Hassan and Al-Sirhan roamed for centuries, stories were carried from tent to tent with the same ease as desert winds. One such tale revolved around a peculiar creature known as Al-Za’boout, a small, hairy, dwarf-like being whose antics were legendary among the Bedouin. He was neither wicked nor monstrous, but rather a walking embodiment of mischief, unpredictability, and the desert’s strange humor.

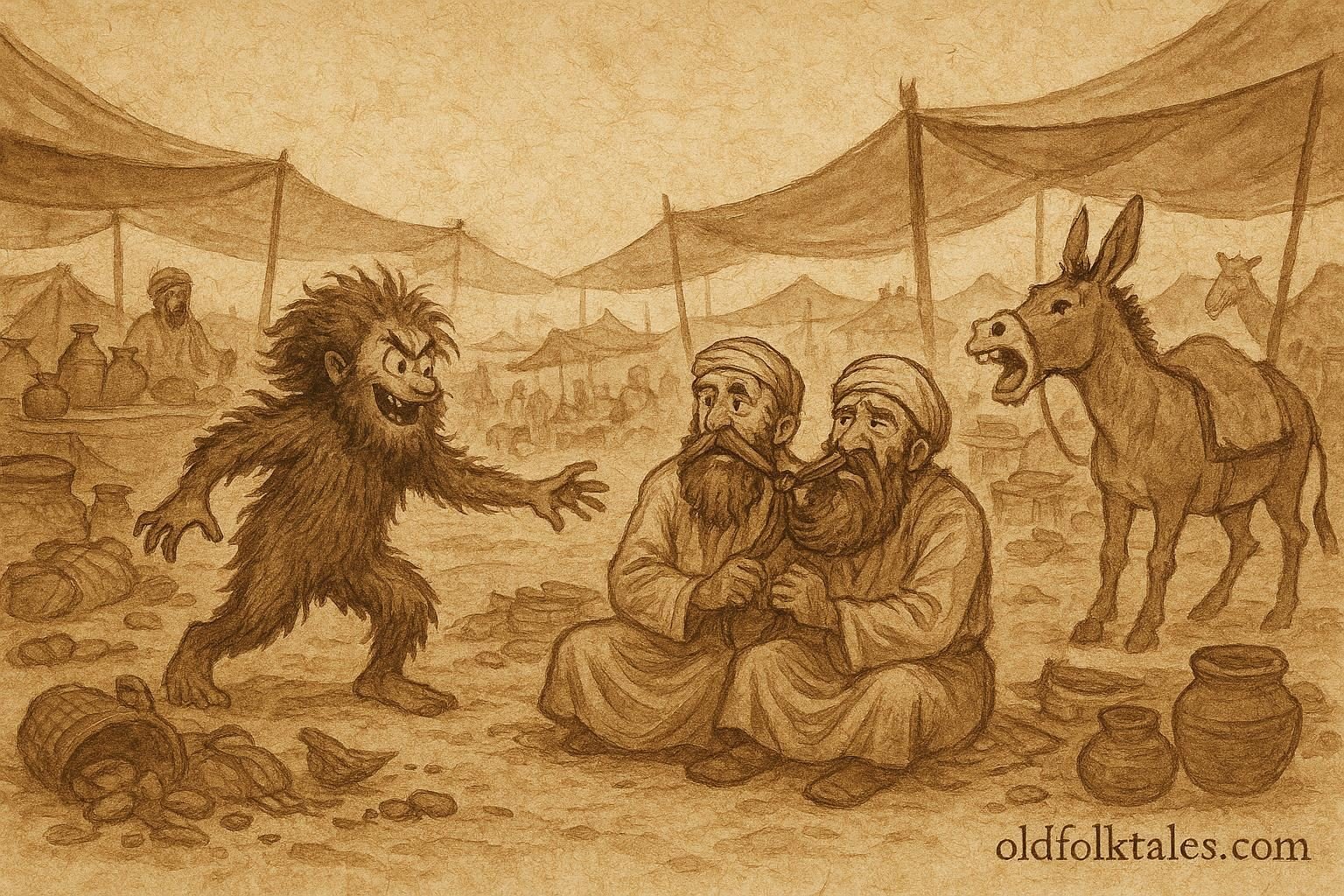

The story takes place in a bustling village marketplace, the kind that came alive every few days when merchants from across the valley and desert gathered to sell their goods. The air filled with shouts of vendors, the scent of roasted nuts, and the braying of donkeys pulling carts. In the middle of all this noise, no one noticed the tiny creature creeping in from behind a stack of woven baskets.

Al-Za’boout was covered in tangled chestnut-colored hair, with eyes that glimmered like mischievous stars. He moved silently, almost too silently, and as soon as his bare feet touched the packed sand of the marketplace, chaos began to unfold.

He started with the merchants who prided themselves on their long, thick beards. With nimble fingers, Al-Za’boout tied the beards of three merchants together while they loudly argued over the price of lentils. When they tried to storm away in different directions, their beards yanked them back into a tangled heap, their shouts echoing through the market and sending the nearby goats into a frantic bleating.

Before anyone could figure out what had happened, Al-Za’boout darted under a fruit stall. With a quick tug, he loosened the wooden beam holding up a basket of figs. When the merchant turned to show a customer the sweetness of his dates, the figs collapsed over his head like a shower of soft missiles. The merchant sputtered furiously, wiping his eyes, while Al-Za’boout stifled a giggle from beneath the stall.

Next, he crawled behind a fabric seller whose brightly colored cloths fluttered in the breeze. Al-Za’boout snatched them one by one, dragging the trailing ends under crates and behind donkeys until the fabric stretched across the path like a giant spiderweb. When the donkeys tried to walk through, they tripped, brayed loudly, and stumbled into one another, making the marketplace erupt in confusion.

Yet the creature’s favorite trick of all involved sound. Al-Za’boout could mimic a donkey’s bray with uncanny skill. Every time a customer tried to haggle, he released a loud, perfectly timed “HEE-HAW!” from somewhere unseen. Offended merchants insisted their donkeys were mocking them; confused customers blamed the merchants; and the real donkeys looked around, bewildered, unsure of who had copied their voice.

The marketplace soon descended into complete disorder. People slipped on fruit, tangled in cloth, tripped over crates, and accused each other of sabotage. Children laughed uncontrollably, recognizing Al-Za’boout’s signature pranks, while adults grew red-faced in frustration.

Despite the chaos, the creature never caused harm, only disorder, embarrassment, and exasperation. In fact, Bedouin storytellers always described him as the reason for mysterious mishaps: missing items, misplaced shoes, ruined cooking pots, or inexplicable noises in the night.

Finally, a wise old man named Abu Rashid stepped forward. Known for his calm nature and quick thinking, he suspected exactly who was behind the uproar. Instead of chasing Al-Za’boout or shouting angrily, he did something unexpected.

He sat down in the center of the marketplace, folded his hands in his lap, and said loudly:

“Al-Za’boout! If you want to bargain, come bargain with me. I have something even your strange humor might appreciate.”

Curiosity, of course, was Al-Za’boout’s greatest weakness. From beneath a pile of spilled chickpeas, his small head popped up. The merchants froze. The children gasped. And the hairy little creature trotted over in full view, his grin wide and playful.

“What deal do you offer, Abu Rashid?” he squeaked.

The old man smiled. “If you stop your mischief for today, I will tell you the funniest story you have ever heard, a tale so ridiculous even you won’t be able to resist laughing.”

Al-Za’boout considered the offer. He loved nothing more than humor, and no one in the market told stories like Abu Rashid. After a long moment, he nodded quickly.

“Deal!”

And just like that, the chaos halted. Beards were carefully untied, donkeys were calmed, fruit was gathered, and fabric was untangled. The marketplace slowly returned to order.

Abu Rashid then told Al-Za’boout a story filled with foolish heroes, talking camels, and impossible coincidences. The creature rolled on the ground laughing, clutching his hairy belly and kicking his feet. When the tale was done, he bowed to the old man and scampered out of the marketplace, leaving behind only whispers, giggles, and a few footprints in the sand.

From that day on, whenever market goods went missing or the donkeys behaved strangely, people simply said, “Al-Za’boout passed through.” And they laughed, because they knew mischief was part of life, and that sometimes, humor was the only way to bring order back to chaos.

Moral Lesson

Even the most disruptive mischief can be tamed through patience, cleverness, and humor. Understanding others—rather than fighting them—creates harmony where anger would fail.

Knowledge Check

1. Who is Al-Za’boout in Bedouin folklore?

A hairy, dwarf-like creature known for harmless but chaotic mischief in desert communities.

2. Where does this folktale originate?

Among Bedouin tribes such as Bani Hassan and Al-Sirhan in the Jordanian Badia.

3. What kind of chaos does Al-Za’boout cause in the marketplace?

He ties merchants’ beards, hides goods, mimics donkey noises, and disrupts stalls.

4. Is Al-Za’boout considered evil?

No. He symbolizes unpredictable mischief, not malice or harm.

5. How is Al-Za’boout subdued in the story?

Through a clever bargain appealing to his sense of humor, offered by Abu Rashid.

6. What is the main lesson of the tale?

Patience and wit resolve problems better than anger or force.

Source

Adapted from the Bedouin folktale “Al-Za’boout in the Marketplace,” preserved among tribes of the Jordanian Badia.