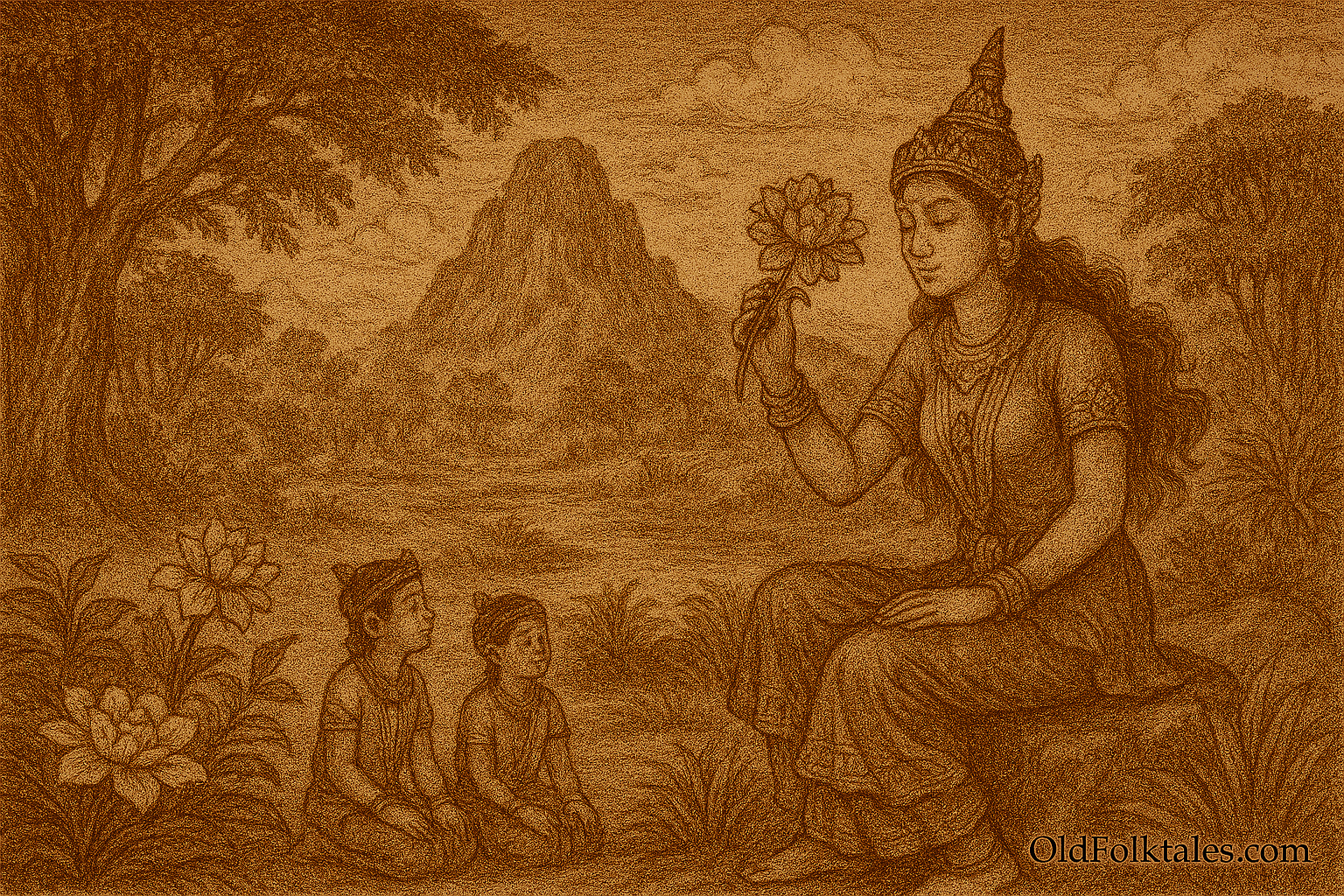

In the time when the boundaries between the human and spirit worlds were more fluid than they are today, when nats walked among mortals and the forests held mysteries beyond human comprehension, there lived a being unlike any other in the wild lands of ancient Burma. She was known as Popa Medaw the Mother of Popa though she had not always borne that sacred title. In her origins, she was something far stranger and more fearsome: a flower-eating ogress who dwelt in the untamed wilderness far from human settlements.

Popa Medaw was not like the demons of nightmares who terrorized villages or devoured livestock. Her nature was more complex, existing in that liminal space between the monstrous and the divine. She sustained herself on flowers not the common blooms that grew in village gardens, but the rare and exotic blossoms that appeared only in the deepest parts of the forest, flowers that glowed with an otherworldly luminescence and carried fragrances that could entrance any creature that breathed their perfume. These magical flowers granted her long life and powers beyond those of ordinary beings, and they imbued her with a strange, terrible beauty that combined the wildness of the forest with an ethereal grace.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

Her domain was the wilderness, and for countless years, she lived apart from the world of humans, content in her solitary existence among the trees, mountains, and mystical flowers that sustained her. But fate, which weaves the threads of all lives together in patterns beyond understanding, had different plans for the flower-eating ogress.

One day, a great king from one of Burma’s powerful kingdoms ventured into the forest on a royal hunting expedition. He was a man of considerable power and status, accustomed to having his commands obeyed and his desires fulfilled. The hunting party pursued their quarry deep into the wilderness, farther than they had ever traveled before, until they found themselves in territories that no longer appeared on any map, the realm where Popa Medaw dwelt.

It was there, in a clearing carpeted with luminous flowers and dappled with golden sunlight filtering through ancient trees, that the king encountered the ogress. What passed between them remains shrouded in the mists of legend whether it was enchantment, genuine affection, or something else entirely but the result was undeniable. The king, despite her otherworldly nature, was drawn to Popa Medaw, and she, for reasons known only to her own heart, allowed herself to be drawn to him in return.

From this impossible union, two sons were born. These were no ordinary children they carried within them the blood of both human royalty and supernatural power. They possessed their father’s noble bearing and their mother’s connection to the spirit world, making them beings of extraordinary potential. The boys grew quickly, displaying abilities that marked them as special: unusual strength, uncanny intuition, and a presence that made even hardened warriors pause with something akin to reverence or fear.

For a time, the family existed in a strange harmony. The king acknowledged his sons and brought them to his palace, where they were raised alongside his legitimate heirs. Popa Medaw herself sometimes visited the human world, though she never fully belonged there. Her wild nature and supernatural origins made her an object of fascination, fear, and most dangerously jealousy among the palace courtiers and the king’s other wives.

The palace was a place of intricate politics, where whispers carried more weight than swords and jealousy could poison the atmosphere more effectively than any venom. The other queens and their families saw Popa Medaw’s sons as threats to their own children’s inheritance and status. Rumors began to circulate dark insinuations about the ogress and her offspring, warnings that children born of such an unnatural union could bring nothing but misfortune to the kingdom.

The jealousy and hostility grew like thorny vines, strangling any possibility of peace. Courtiers who sought favor with the other queens added their voices to the chorus of suspicion. They pointed to every small misfortune as evidence of supernatural malevolence, blamed every failed harvest or military setback on the presence of the ogress’s children in the palace. The whispers became open accusations, and the accusations became demands for exile.

Even the king, who had once been captivated by the flower-eating ogress, could not forever withstand the pressure from his court. The weight of political reality pressed down upon whatever affection or fascination he had felt. Torn between his supernatural family and the stability of his kingdom, he made a choice that would echo through the centuries he turned away from Popa Medaw and her sons.

Popa Medaw, sensing the hostility that now surrounded her like a storm cloud and recognizing that her presence had become a source of danger rather than joy, made the decision to leave. She would not stay where she was unwanted, would not expose her sons to the poison of palace jealousy. With a mother’s fierce protective love overriding any other consideration, she gathered her children and fled from the palace, leaving behind the world of human politics and returning to the realm of the wild.

Her destination was Mount Popa, a volcanic peak that rose from the plains like a sacred pillar connecting earth and sky. The mountain had always been a place of power, a site where the spirit world pressed close to the mortal realm. Its slopes were covered with lush vegetation, its summit often wreathed in mist, and its caves and grottoes were said to be dwelling places of ancient spirits. If anywhere could provide sanctuary for a being like Popa Medaw, it was this sacred mountain.

But the journey took its toll. Whether from exhaustion, heartbreak, or the simple wearing down of her supernatural vitality, Popa Medaw died upon reaching Mount Popa. Her death, however, was not an ending but a transformation. The flower-eating ogress who had loved a king and borne two extraordinary sons did not simply cease to exist instead, she underwent a metamorphosis that reflected her true nature and the sacred power that had always resided within her.

Popa Medaw became a nat, a powerful protective spirit whose domain was Mount Popa itself. No longer bound by mortal flesh, she transformed into something greater: the Mother Spirit of the mountain, a guardian whose influence would extend across all of Burma. Her death was mourned, but her transformation was celebrated, for she had become one of the most powerful nats in the Burmese pantheon, a spirit to whom people could pray for protection, blessing, and intervention.

Her sons, inheriting both their mother’s supernatural nature and their father’s royal blood, also underwent transformation. They too became nats, joining their mother in the spirit realm and taking their places among the Thirty-Seven Nats the official pantheon of spirits revered throughout Burma. Together, mother and sons formed a sacred family that would be honored for generations, their story becoming foundational to Burmese spiritual practice.

Mount Popa itself became the center of nat worship in Burma, a pilgrimage site where people would climb the hundreds of steps carved into the volcanic rock to reach the shrines and temples at its summit. There, they would make offerings to Popa Medaw and her sons flowers (in memory of her flower-eating origins), food, gold leaf, and prayers. Annual festivals would draw thousands of devotees who came to honor the Mother of Popa and seek her blessing.

The legend explains not only the origin of these powerful spirits but also the deep connection between Mount Popa and spiritual practice in Myanmar. Even today, the mountain remains a sacred site, and Popa Medaw continues to be revered as a powerful protective spirit. Her story from flower-eating ogress to divine mother speaks to the possibility of transformation, the power of maternal love, and the thin veil that separates the mortal and spirit worlds in Burmese cosmology.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

The legend of Popa Medaw teaches that transformation can emerge from suffering, and that rejection in one realm can lead to elevation in another. It shows how maternal love transcends boundaries between worlds and how beings who do not fit within conventional society can find their true purpose and power elsewhere. The story also illustrates the Burmese understanding that spirits are not simply abstract forces but have histories, emotions, and relationships that make them worthy of respect and devotion. Finally, it reminds us that what appears as an ending death, exile, rejection can actually be a transformation into something more powerful and enduring than what came before.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Popa Medaw before she became a nat spirit in Burmese mythology?

A1: Popa Medaw was originally a flower-eating ogress who lived in the wilderness of ancient Burma, sustaining herself on rare, magical flowers that grew in the deepest forests. She possessed supernatural powers and existed in a liminal space between the monstrous and the divine before her encounter with a human king changed her destiny.

Q2: How did Popa Medaw come to have two sons with a human king?

A2: During a royal hunting expedition, a powerful king ventured deep into the wilderness where Popa Medaw dwelt. They encountered each other in a clearing, and despite her otherworldly ogress nature, a connection formed between them. From this union between human royalty and supernatural being, two sons were born who carried both mortal and spirit blood.

Q3: Why did Popa Medaw flee from the palace to Mount Popa?

A3: Popa Medaw fled because of intense jealousy and hostility from the other queens and palace courtiers who viewed her and her sons as threats and unnatural presences. The poisonous atmosphere of suspicion and accusation, combined with the king’s inability to protect them from palace politics, made her realize that staying would endanger her children, prompting her protective maternal decision to leave.

Q4: What happened to Popa Medaw when she reached Mount Popa?

A4: Upon reaching Mount Popa, Popa Medaw died from exhaustion, heartbreak, or the wearing down of her supernatural vitality. However, her death was a transformation rather than an ending she became a powerful nat (protective spirit), specifically the Mother Spirit of Mount Popa, one of the most revered spirits in the Burmese pantheon.

Q5: What is the significance of Popa Medaw’s sons in Burmese nat worship?

A5: Popa Medaw’s two sons also became nats after their mother’s transformation, joining her in the spirit realm. They became two of the Thirty-Seven Nats the official pantheon of spirits revered throughout Burma. Together with their mother, they form a sacred family that is central to Burmese spiritual practice, particularly at Mount Popa.

Q6: How does the legend of Popa Medaw explain Mount Popa’s spiritual importance in Myanmar today?

A6: The legend establishes Mount Popa as the dwelling place and transformation site of Popa Medaw, making it the sacred center of nat worship in Myanmar. The mountain became a major pilgrimage site where devotees climb to shrines honoring Popa Medaw and her sons, making offerings and seeking blessings during annual festivals. The legend provides the spiritual foundation for Mount Popa’s continuing importance in Burmese religious practice.

Cultural Origin: Burmese nat (spirit) tradition and mythology, Myanmar (Burma), Southeast Asia