In the bustling coastal cities of the Hijaz, where the Red Sea breeze carries the scents of spice markets, fishermen’s nets, and simmering pots, lived Juha, the timeless trickster of Arab folklore. He was known throughout the region for his cleverness, his humor, and his constant struggle with poverty, which he bore with remarkable cheerfulness.

Juha’s home was a small, weathered dwelling squeezed between the larger houses of wealthier families. Although his means were limited, his spirit was never dimmed. He often said, “A full heart is better than a full purse,” a phrase that puzzled his neighbors but comforted him on the days when even bread was scarce.

One warm afternoon, as the sun dipped low and the city streets filled with evening chatter, Juha returned home hungry and tired. All he had for supper was a small piece of dry, hard bread, so stale it could barely be bitten. Still, Juha sat outside his doorway and prepared to make the most of it.

Just then, a rich, mouthwatering aroma drifted through the narrow alley. It was Kabsa, the beloved Hijazi dish of rice and meat simmered with fragrant spices, cardamom, black lime, cinnamon, and cloves. The scent was unmistakable, filling the air with warmth and longing.

Juha closed his eyes, lifted his chin slightly, and began to inhale deeply. With every breath, his bread seemed a little less dry. He imagined the flavors of the kabsa blending with his humble meal, and for a moment, he felt satisfied.

Unfortunately for him, the aroma came from the kitchen of his wealthy neighbor, a man known not only for his riches but also for his pettiness. When the neighbor saw Juha standing by the window taking in the scent of the dish, he burst from his doorway with indignation.

“Juha!” he shouted. “Are you stealing the smell of my kabsa?”

Juha blinked in surprise. “Stealing? My friend, I am merely breathing the air that God placed between us.”

But the neighbor was not one to be soothed. Upset that his cooking brought joy to someone else for free, he declared, “I will not have you enjoy what you did not pay for! You shall compensate me for the scent you have taken.”

Juha laughed softly, thinking it a joke. It was not.

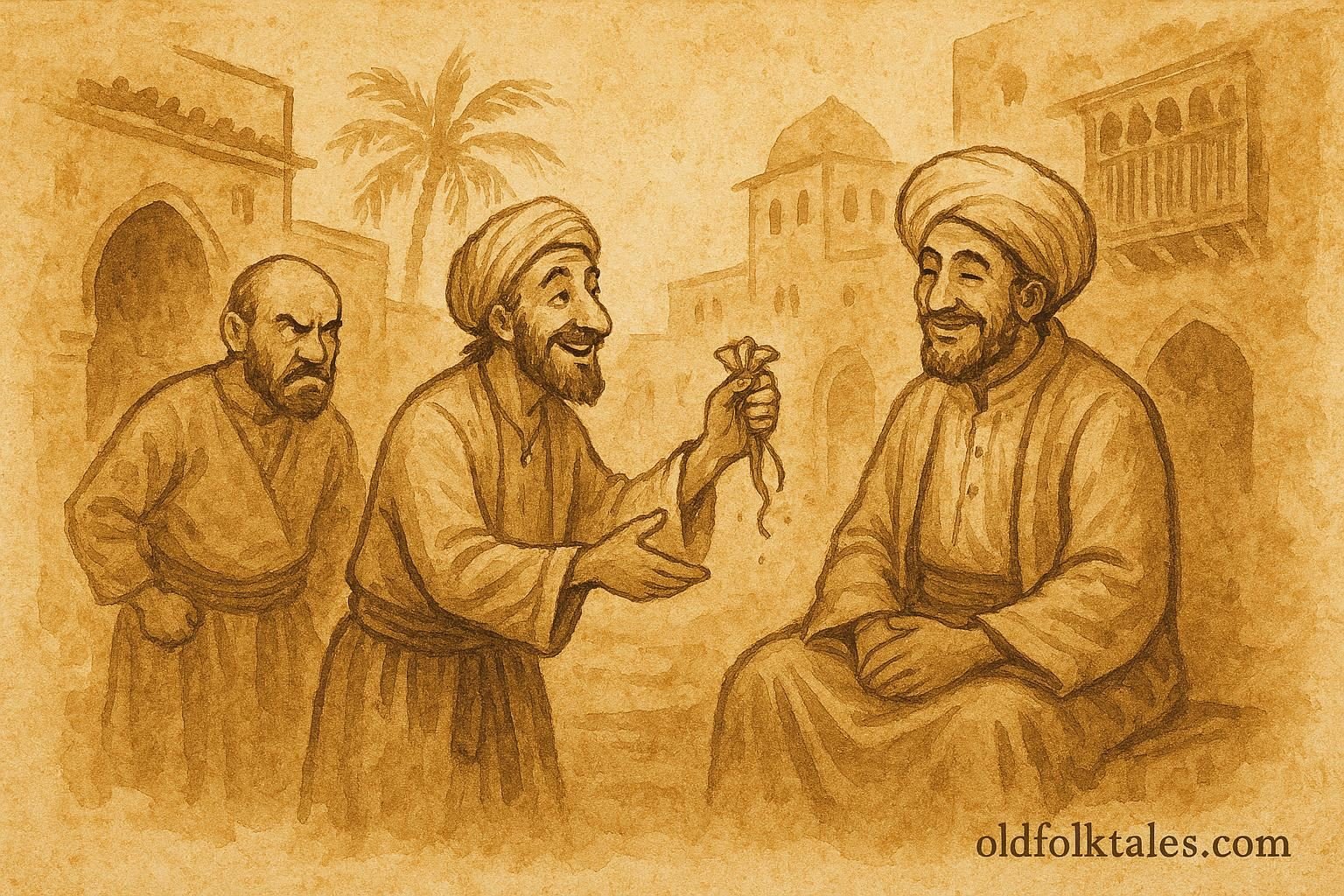

The neighbor grabbed Juha by the arm and dragged him through the streets, past merchants closing their stalls and children playing with pebbles, until they reached the Qadi, the local judge known for his fairness and wisdom.

Inside the simple wooden courtroom, the Qadi looked up calmly as the disgruntled neighbor presented his unusual complaint.

“Your Honor,” he said dramatically, “Juha has stolen something valuable from me. He has stolen the smell of my food!”

The Qadi raised an eyebrow. “The smell?”

“Yes!” the neighbor insisted. “He stood at my window inhaling it as if it belonged to him!”

A quiet murmur passed through the room. Some people fought back laughter; others simply shook their heads. Juha stood humbly, waiting for the judge’s decision.

“Juha,” said the Qadi gently, “what do you have to say about this accusation?”

Juha bowed his head respectfully. “Your Honor, I have eaten nothing, taken nothing, touched nothing. I only breathed the air that moved freely through the alley.”

The Qadi stroked his beard in thought. “A curious matter,” he mused. Then suddenly, he said, “Juha, do you have any money on you?”

Juha reached into his pocket and produced a small pouch containing a few coins, the entirety of his savings. He held it in his hand, unsure of what the judge intended.

“Shake it,” the Qadi instructed.

Juha obeyed. The coins clinked and chimed, their metallic tones filling the courtroom with bright echoes.

The judge turned to the neighbor. “Did you hear the sound of the coins?”

“Yes,” the neighbor replied, puzzled.

“Very well,” said the Qadi. “The sound of Juha’s coins shall pay for the smell of your kabsa.”

The room erupted into laughter, soft at first, then uncontrollable. Even the Qadi allowed himself a smile.

The neighbor’s face flushed with embarrassment, for he now realized how foolish his complaint sounded. Still, he could not argue. The logic was perfect. The judgment stood.

The Qadi dismissed the case with a wave of his hand. “Go home, Juha,” he said kindly. “And you,” he added to the neighbor, “learn that some grievances are made of nothing but air.”

Juha thanked the judge, tucked his pouch of coins safely away, and walked home with light steps. That evening he ate his dry bread with renewed gratitude, smiling at the absurdity of the day.

And from that moment onward, the story spread throughout the Hijaz, told in markets, recited at gatherings, and cherished for its humor and its wisdom. Whenever someone complained too much over a trivial matter, elders would say, “Beware, lest you become like the man who charged for the smell of kabsa!”

Moral of the Story

Greed makes even the simplest blessings seem like losses. True wisdom recognizes that some things, like air, scent, and kindness, belong to everyone.

Knowledge Check

1. Why did the neighbor accuse Juha in this Hijazi folktale?

Because he believed Juha was “stealing” the smell of his kabsa.

2. What traditional dish creates the central conflict in the story?

Kabsa, the spiced rice and meat dish beloved in the Hijaz region.

3. How does the Qadi resolve the dispute between Juha and the neighbor?

By ruling that the sound of Juha’s coins pays for the smell of the neighbor’s food.

4. What cultural value is highlighted through Juha’s clever response?

The importance of humor, logic, and fairness in solving disputes.

5. What does the greedy neighbor symbolize in Arabian folklore?

The folly of pettiness and material obsession.

6. What moral teaching does the Hijazi version of Juha convey?

Not all grievances deserve attention; some complaints are empty and baseless.

Source

Adapted from the Hijazi variant of the Juha folktale as referenced in Saudi Arabia: Folk Stories & Folk Songs by Ali H. Al-Halawani, with support from traditional Pan-Arab oral lore.