In the towns and villages of Uzbekistan, where caravan roads once crossed and voices gathered in teahouses, there lived a man whose wisdom arrived wrapped in laughter. His name was Khoja Nasreddin, and though he owned little, his words traveled far. Some called him foolish, others clever, but all who listened soon learned that his humor carried sharp truth.

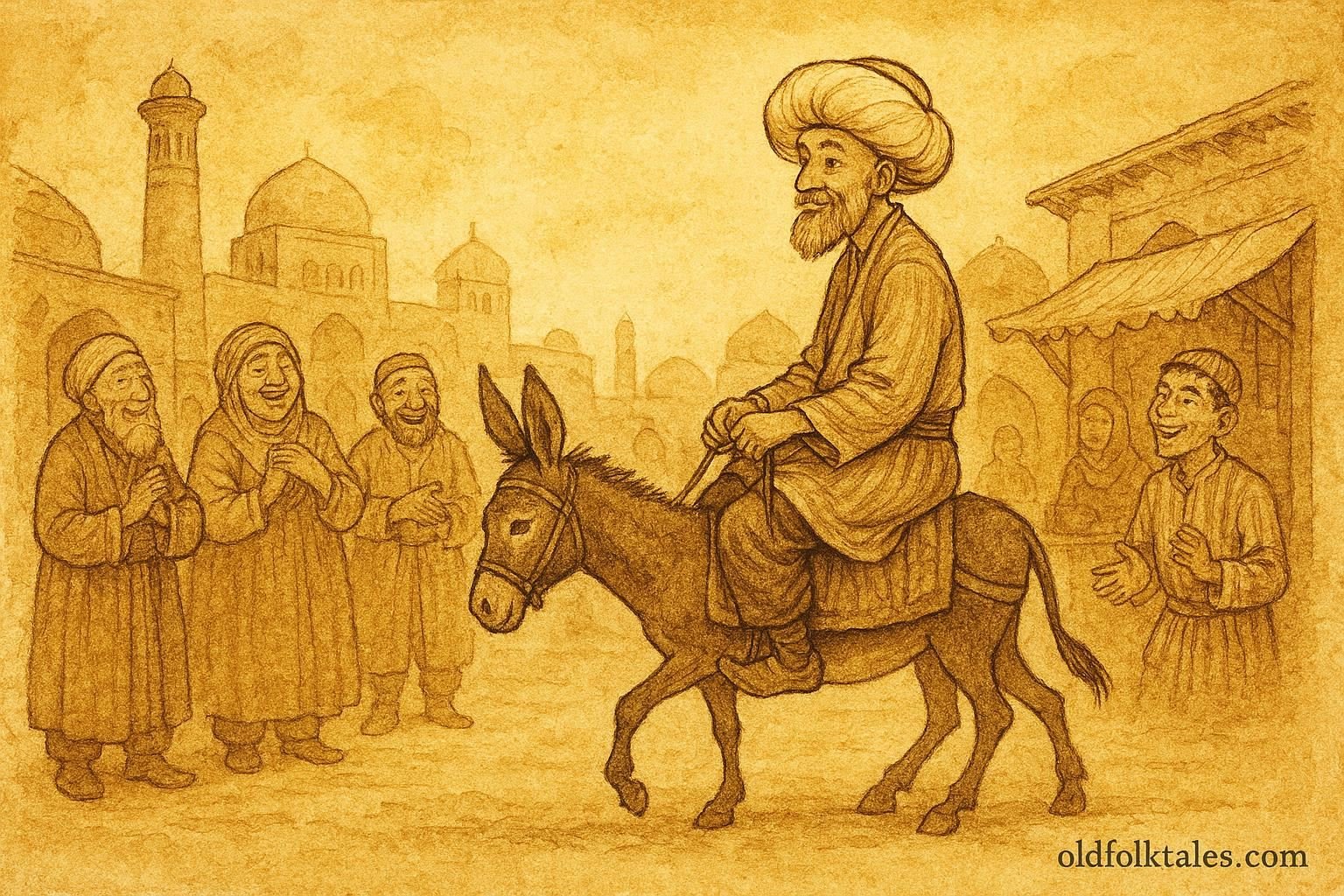

Khoja Nasreddin dressed simply and often rode a small donkey through the marketplace. One day, villagers laughed when they saw him riding the donkey backward, facing the animal’s tail rather than its head. Children mocked him, and passersby shook their heads, whispering that the Khoja had finally lost his sense.

When questioned, Nasreddin smiled and replied calmly, “I am not backward. It is the world that moves in strange directions. This way, I can see where I have been and where I am going.” His answer silenced the crowd, for beneath the humor lay a lesson about perspective and judgment.

In another tale, Nasreddin was summoned before a powerful local ruler who prided himself on intelligence and authority. The ruler wished to test the Khoja and embarrass him publicly. He asked questions meant to confuse and trap him. Instead of answering directly, Nasreddin responded with questions of his own—simple, innocent-sounding questions that revealed the ruler’s arrogance and lack of self-awareness.

At one point, the ruler demanded to know how many stars were in the sky. Nasreddin answered, “As many as there are hairs on my donkey.” When the ruler scoffed, Nasreddin replied, “Count them if you doubt me.” The court erupted in laughter, and the ruler, exposed but unable to punish wit, was forced to retreat in silence.

Nasreddin’s stories were not only for rulers. In the marketplace, he often pretended to be foolish so that greedy merchants would reveal their dishonesty. In one tale, he asked for soup from a rich man’s pot, holding his bread over the steam instead of dipping it into the broth. When the merchant protested, Nasreddin replied, “If you charge money for the soup, then steam is all I can afford.” Once again, laughter delivered justice where force could not.

Despite his cleverness, Nasreddin never claimed superiority. He often placed himself at the center of the joke, reminding listeners that wisdom begins with humility. His humor softened harsh truths, making them easier to accept and harder to ignore.

These stories traveled orally, from elders to children, from travelers to villagers, shaping moral thought without sermons. Through donkey rides, riddles, and playful defiance, Khoja Nasreddin showed that laughter can challenge power, and that true intelligence does not shout, it smiles.

Moral Lesson

The tales of Khoja Nasreddin teach that wisdom thrives in humility, justice can be delivered through humor, and authority should always be questioned with intelligence rather than fear.

Knowledge Check

-

Q: Who is Khoja Nasreddin in Uzbek folklore?

A: A wise trickster figure who teaches moral lessons through humor and paradox. -

Q: Why does Nasreddin ride his donkey backward?

A: To show that perspective matters and judgments are often misleading. -

Q: How does Nasreddin confront unjust authority?

A: Through wit, clever speech, and harmless humor rather than force. -

Q: What role does humor play in these tales?

A: Humor delivers moral truth in a way that is memorable and non-threatening. -

Q: Where were Nasreddin stories traditionally shared?

A: In marketplaces, teahouses, and village gatherings. -

Q: What core values do these tales promote?

A: Humility, justice, wisdom, and critical thinking.

Source: Central Asian oral tradition; widely documented folklore cycle.

Cultural Origin: Uzbekistan (Uzbek folk tradition)