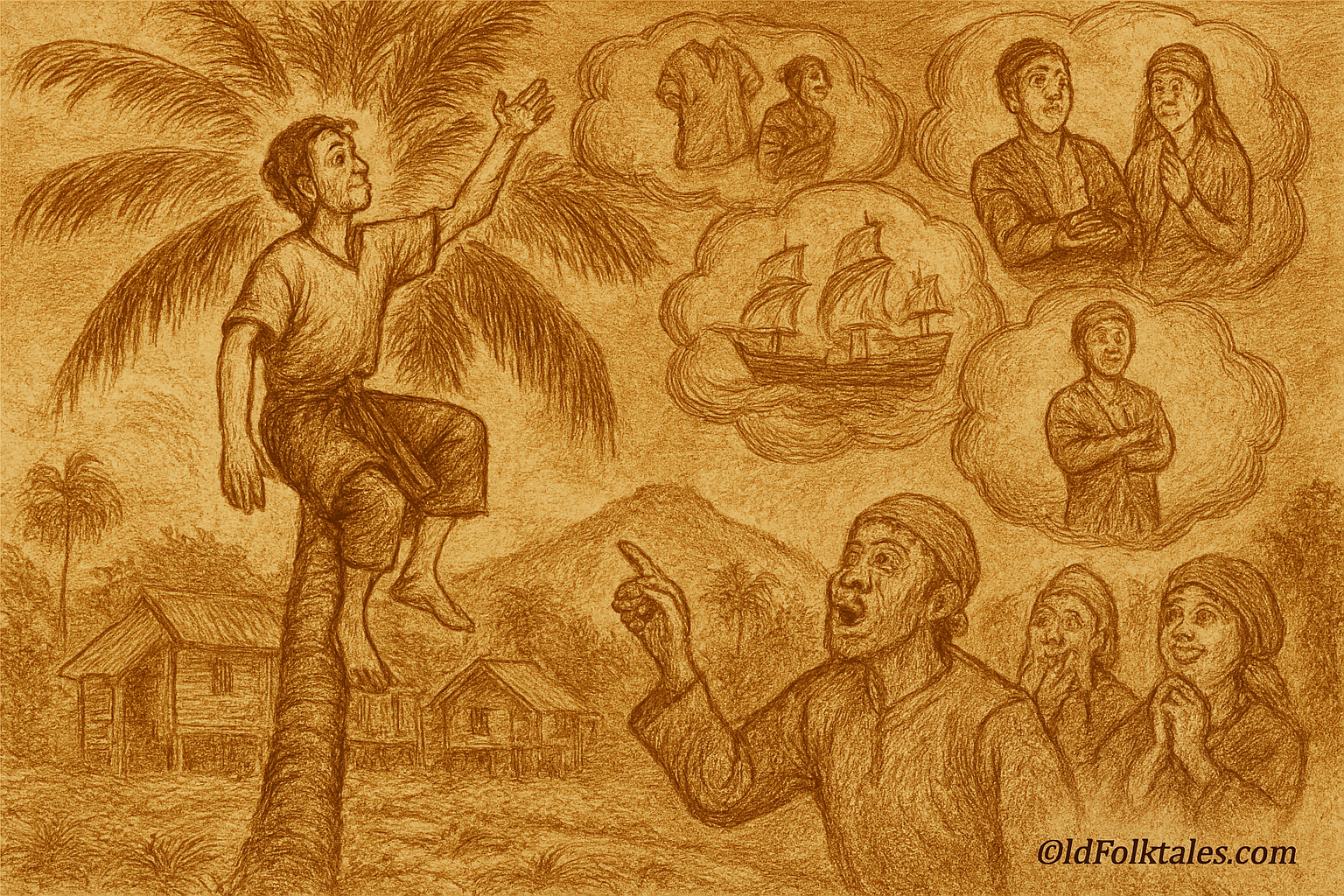

In a sun-drenched village nestled among the coconut groves and rubber plantations of the Malay Peninsula, there lived a young man named Mat Jenin. He was the sort of fellow everyone knew, and most people liked cheerful, quick with a smile, always ready with a joke or a friendly word. His laughter rang out easily, his spirits rarely flagged, and he moved through life with an optimism that seemed unshakeable, even when circumstances suggested he should be more concerned.

Mat Jenin was not lazy, exactly. He took on odd jobs around the village with genuine willingness. He would help farmers harvest their rice, assist fishermen with their nets, chop firewood for elderly neighbors, or climb the tall coconut palms that swayed in the coastal breeze to collect the precious fruits that grew in clusters beneath their fronds. The problem was not that Mat Jenin refused to work it was that he could never seem to keep working once he had earned a little money.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

The moment a few coins clinked into his palm, his mind would wander off like a kite cut loose from its string. He would sit beneath a shady tree, the unfinished task forgotten, his eyes glazed with the unmistakable look of someone whose spirit had left the present moment and soared into realms of pure imagination. His fellow villagers would shake their heads knowingly. “There goes Mat Jenin again,” they would say with affectionate exasperation, “lost in his dreams.”

One particularly bright morning, when the sun painted everything golden and the air smelled of frangipani blossoms and salt from the distant sea, Mat Jenin received a job from Pak Hassan, a prosperous coconut plantation owner. The task was straightforward enough: climb the coconut trees, harvest the ripe fruits, and collect them in baskets below. For each tree completed, Mat Jenin would earn a fair wage enough to buy rice, salted fish, and perhaps even some sweet kuih cakes from the market.

Mat Jenin approached the first tree with his usual enthusiasm. It was a magnificent specimen, rising perhaps forty feet into the air, its rough bark scarred by years of climbers. He tied a rope around his waist in the traditional way, braced his bare feet against the trunk, and began the ascent. His muscles worked smoothly, his movements practiced and confident. Within minutes, he reached the crown where the heavy coconuts hung in green and brown clusters.

He began to work, using his parang the traditional curved knife all coconut harvesters carried to cut the stems. Each coconut fell with a satisfying thud onto the soft earth below. One coconut. Two coconuts. Three coconuts. With each successful cut, the small pile on the ground grew larger.

And with it, Mat Jenin’s imagination began to stir.

He paused in his work, one hand gripping a coconut, the other holding his parang, and allowed his mind to wander down a tantalizing path. “These coconuts,” he thought, “are of excellent quality. When I sell them at the market, I will surely earn good money. Perhaps five or six ringgit, maybe more.”

His hands continued working automatically while his consciousness drifted deeper into fantasy. “Yes, with five ringgit, I could buy cloth not the cheap cotton, but fine batik fabric, perhaps even silk. I would have a beautiful new sarong made, one with intricate patterns of gold and crimson that catch the eye.”

The coconuts kept falling, thudding rhythmically below, but Mat Jenin no longer truly heard them. He was climbing not a tree but a ladder of dreams, each rung taking him higher into improbable grandeur.

“When I wear such a fine sarong,” he continued in his reverie, “I would stand out at the village gathering. The penghulu the village chief himself would notice me. He would say, ‘Mat Jenin, you are clearly a young man of taste and ambition. I have been looking for someone like you.’ And perhaps he would introduce me to his household.”

Mat Jenin’s eyes had taken on a distant, glassy quality. His smile widened as the fantasy elaborated itself with ever more ornate detail.

“The chief’s daughter! Of course! The beautiful Siti Aminah, with her graceful walk and gentle voice. Once she sees me in my fine clothes, looking prosperous and confident, how could she not be impressed? We would marry with the entire village celebrating. Her father would give us his blessing and perhaps a generous gift land, or money, or both!”

The breeze shifted, causing the palm tree to sway slightly, but Mat Jenin barely noticed. He was far away now, living in a future that felt more real than the bark beneath his feet.

“With wealth from my marriage, I could start a business. Not just any business I would become a trader! I would buy a boat, then two boats, then an entire fleet! I would sail to Sumatra, to Java, to distant Singapore and beyond. My ships would be filled with spices, fine cloth, precious woods. Other traders would know my name and respect me. ‘There goes Mat Jenin,’ they would say, ‘the most successful merchant on the peninsula!'”

His chest swelled with pride at this imagined future. He could see it all so clearly: himself standing on the deck of his ship, dressed in expensive clothes, respected and admired by all who knew him. He was no longer a simple coconut harvester he was Mat Jenin the Magnificent, Mat Jenin the Prosperous, Mat Jenin whose name was spoken with reverence!

In his excitement, caught up in the crescendo of his fantasy, Mat Jenin threw his arms wide in a gesture of triumph, as if embracing all the success and glory his imaginary future held.

And in that moment, he forgot one crucial detail: he was still forty feet above the ground, clinging to a swaying coconut palm.

His rope loosened. His feet lost their grip on the trunk. For one suspended heartbeat, Mat Jenin hung in the air, his face still wearing that expression of dreamy triumph. Then gravity reasserted its ancient authority, and he plummeted earthward like a stone.

He crashed through the palm fronds, his body striking branches and trunk on the way down, before landing with a heavy, sickening thud in the pile of coconuts he had harvested. The impact knocked the breath from his lungs and sent sharp pain shooting through every limb. He lay there, groaning, surrounded by the fruits of his actual labor, his grand dreams scattered like morning mist under the harsh sun of reality.

Pak Hassan and other villagers came running at the sound of the fall. They found Mat Jenin bruised, battered, and barely conscious, but mercifully without broken bones the pile of coconuts had cushioned his fall just enough to save him from more serious injury.

For weeks afterward, Mat Jenin lay recuperating in his small house, every movement accompanied by pain and stiffness. Neighbors brought him food and checked on his recovery, but they also couldn’t resist teasing him gently about his spectacular fall.

“Were you dreaming again, Mat Jenin?” they would ask with knowing smiles.

“What great fortune did you see in your future this time?”

“Did your imaginary ships sail too close to the sun?”

Mat Jenin, to his credit, could only laugh ruefully along with them, though the laughter made his ribs ache. He had learned his lesson in the hardest possible way: dreams are beautiful things, but they make poor handholds when you’re climbing a tree.

From that day forward, whenever someone in the village or anywhere in Malaysia spoke of grand plans built entirely on wishful thinking, with no foundation in present action, they would invoke Mat Jenin’s name. “That’s just angan-angan Mat Jenin,” they would say, shaking their heads with amusement. “Mat Jenin’s daydreams.”

The phrase spread beyond that single village, becoming woven into the fabric of Malay language and culture. It serves as a gentle but pointed reminder: dream big, yes, but keep your feet firmly planted on the ground or at least keep one hand gripping the tree you’re climbing. Vision without action is merely hallucination, and the fall from fantasy to reality can be painful indeed.

Mat Jenin recovered fully, and he continued to work in the village for many years. People say he remained a dreamer at heart, but afterward, he made sure to sit down before allowing his imagination to carry him away. After all, some lessons are too painful to need repeating.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral of the Story

This Malaysian folktale teaches us that while ambition and imagination are valuable qualities, they must be balanced with attention to present reality and practical effort. Mat Jenin’s elaborate fantasy distracted him from the task at hand, leading to painful consequences. Dreams should inspire us to work harder, not replace the work itself. The story reminds us to pursue our goals with both vision and groundedness to keep one foot in the future we hope to create while firmly planting the other in the present moment where actual progress happens. Success requires not just dreaming but doing.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Mat Jenin in Malaysian folklore?

A: Mat Jenin is a cheerful but easily distracted young man from a Malay village who is known for his vivid daydreams and fantasies. While not lazy, he stops working whenever he earns money and loses himself in elaborate dreams about becoming wealthy and successful.

Q2: What job was Mat Jenin doing when he had his famous fall?

A: Mat Jenin was harvesting coconuts from tall coconut palms for Pak Hassan, a plantation owner. He was climbing a tree approximately forty feet high, cutting down ripe coconuts and collecting them in baskets below for payment.

Q3: What fantasy did Mat Jenin imagine while in the coconut tree?

A: Mat Jenin imagined an elaborate progression from selling coconuts, to buying fine batik or silk cloth, to impressing the village chief (penghulu), to marrying the chief’s beautiful daughter Siti Aminah, to becoming a wealthy merchant with a fleet of trading ships sailing throughout Southeast Asia.

Q4: What does “angan-angan Mat Jenin” mean in Malay culture?

A: “Angan-angan Mat Jenin” translates to “Mat Jenin’s daydreams” and is a proverb used throughout Malaysia to describe grand plans or fantasies that are unrealistic, built on wishful thinking rather than concrete action, or dreams that distract from present responsibilities.

Q5: Why did Mat Jenin fall from the coconut tree?

A: Mat Jenin became so absorbed in his elaborate fantasy of future wealth and success that he forgot where he was. In a moment of excitement, he threw his arms wide in a gesture of triumph, releasing his grip on the tree and falling forty feet to the ground.

Q6: What cultural values does this story reflect about Malay society?

A: The story emphasizes the importance of balancing ambition with practical action, staying grounded in present reality while working toward future goals, and the value of honest, sustained effort over idle fantasizing. It reflects traditional Malay values of diligence, mindfulness, and the wisdom of keeping dreams tethered to reality.

Source: Adapted from Malay Folklore and Proverbs by R.O. Winsted

Cultural Origin: Malay people, Peninsular Malaysia