The river that flowed through the village had been there longer than anyone could remember, its murky waters carrying stories from the highlands to the sea. The elders spoke of it with reverence, calling it Sungai Bertuah, the blessed river that gave life through its fish and fertility through its seasonal floods. But they also spoke of it with caution, for the river had another nature, a darker side that demanded respect and obedience to ancient rules passed down through countless generations.

Si Malang was a fisherman who had grown up hearing these warnings, yet he had never truly believed them. His name, which meant “unfortunate” or “unlucky,” had been given to him by his grandmother who claimed to have seen omens at his birth. But Si Malang scorned such superstitions, considering himself a practical man governed by reason rather than old wives’ tales.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

He was skilled at his trade, there was no denying that. His nets always seemed to come up heavy with fish, and he knew the river’s moods better than most. But his success had bred in him a dangerous arrogance, a belief that he had mastered the river through skill alone, with no debt owed to the spirits that the old people insisted dwelled in its depths.

The village elders had clear rules about the river. There were sections where fishing was forbidden during certain moon phases. There were places where one must never swim, particularly the deep pool near the bend where the water ran dark and still. Offerings of rice and flowers were to be made at the river’s edge each month, acknowledgments to the spirits and their crocodile guardians who protected the waters.

“Foolishness,” Si Malang would mutter when he saw others making their offerings. “The crocodiles are just animals. They have no spiritual power. They attack because they’re hungry, not because anyone has disrespected spirits.”

His wife, a quiet woman named Minah, would plead with him to show more caution. “The traditions exist for a reason, husband. Our grandparents and their grandparents before them observed these rules. Why do you think you know better?”

But Si Malang would laugh dismissively. “Because I have eyes and a mind. I see a river, not a temple. I see crocodiles, not gods. All this talk of guardian spirits is just a way to keep people fearful and obedient.”

The village bomoh, Tok Ibrahim, tried to counsel Si Malang after hearing of his disrespectful words. The old spiritual healer invited the fisherman to his home, served him tea, and spoke gently about the nature of the river.

“The spirits are not separate from the crocodiles,” Tok Ibrahim explained, his weathered hands wrapped around his own clay cup. “They inhabit them, work through them. The crocodiles are both animal and guardian, both creature and keeper of sacred boundaries. When we respect the taboos, we acknowledge this dual nature and keep ourselves safe.”

Si Malang listened politely but remained unconvinced. “With respect, Tok, I have fished that river my entire life. I’ve seen crocodiles. They’re dangerous, yes, but only when you’re careless. There’s no magic involved, just common sense.”

Tok Ibrahim’s eyes grew sad. “Pride is a heavy burden, Si Malang. It blinds us to truths that could save our lives. Please, I beg you, observe the taboos. If not for belief, then for safety. If not for yourself, then for your family.”

But Si Malang left the bomoh’s house unchanged in his views, perhaps even more determined to prove that the old ways were unnecessary superstition.

The crisis came on a particularly hot afternoon when the sun beat down mercilessly and the air hung thick and still. Si Malang had spent the morning fishing with moderate success, but the heat had left him sweaty and irritable. He decided to cool off with a swim, and his eyes fell on the forbidden pool, the deep, dark bend where the elders always warned against entering.

Several younger men from the village were nearby, mending their nets in the shade. They looked up in alarm as Si Malang began removing his shirt and wading toward the forbidden area.

“Brother Malang!” one of them called out. “You cannot swim there! That is the guardians’ territory!”

Si Malang turned with a mocking grin. “Watch me. I’ll prove there’s nothing to fear from these so called guardian spirits.”

“Please,” another young man pleaded. “At least make an offering first. Show some respect.”

“Respect for what?” Si Malang laughed loudly. “For fairy tales? For crocodiles with delusions of divinity?” He cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted toward the water: “Spirits of the river! Guardian crocodiles! I, Si Malang, enter your sacred pool! Strike me down if you can!”

The young men backed away, horrified at this open blasphemy. The air itself seemed to grow heavier, the stillness more profound. Even the birds stopped their afternoon chatter.

Si Malang waded deeper into the forbidden pool, the cool water rising to his waist, then his chest. He floated on his back, laughing at the sky. “You see? Nothing happens! It’s all nonsense!”

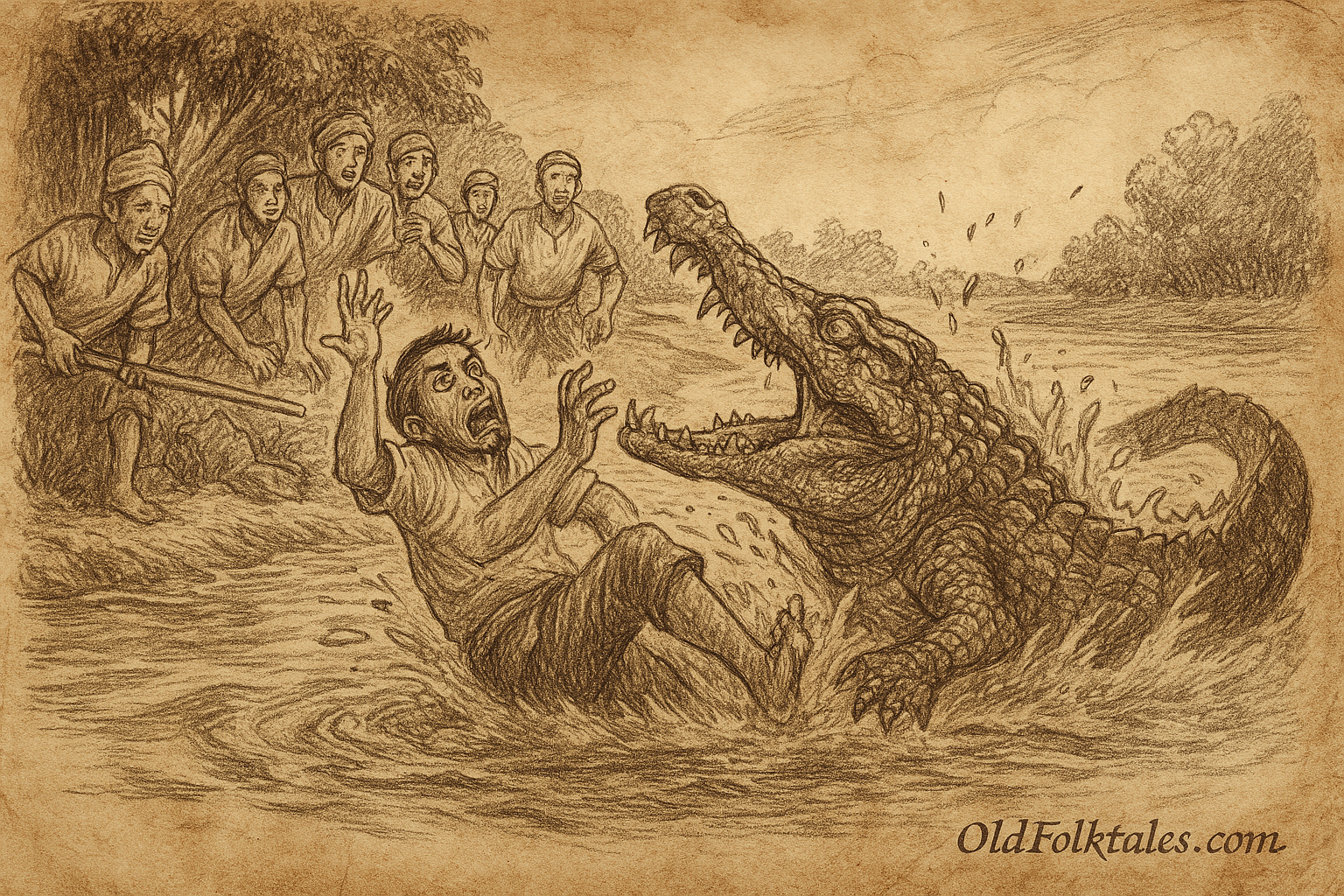

That was when the water around him exploded.

A massive crocodile, larger than any Si Malang had ever seen, erupted from the depths. Its jaws were lined with teeth like daggers, its eyes were cold and ancient, reflecting knowledge that predated human memory. The creature’s tail lashed the water into violent foam as it lunged toward the fisherman.

Si Malang’s mockery died in his throat, replaced by a scream of pure terror. He thrashed toward the shore, but the crocodile was impossibly fast. He felt teeth graze his leg, felt the power of jaws that could snap a man in half like a dry twig. The water churned red with his blood.

The young men on shore, despite their fear, grabbed long bamboo poles and rushed into the shallows, shouting and striking the water. Their bravery distracted the crocodile for a crucial moment, long enough for Si Malang to drag himself onto the muddy bank, his leg torn and bleeding.

The crocodile did not pursue onto land. It remained in the water, its massive head breaking the surface, its ancient eyes fixed on Si Malang with what seemed like intelligent judgment rather than mere predatory hunger. Then it sank back into the depths, leaving only ripples that spread across the forbidden pool like accusations.

Si Malang lay on the riverbank, gasping and bleeding, surrounded by the young men who had risked their lives to save him. His arrogance had fled with his blood, replaced by shock and dawning horror at what he had done.

Tok Ibrahim was summoned and came quickly, his medicine bag in hand. As he cleaned and bound the terrible wounds, he spoke quietly to the semiconscious fisherman.

“You are alive only because those young men intervened and because the guardian chose to spare you. This was a warning, Si Malang. The river has shown you mercy this time, but mercy offered and rejected becomes justice served.”

In the days that followed, as Si Malang’s wounds slowly healed, he had much time to reflect. He realized that his arrogance had not only endangered himself but also the young men who had felt obligated to rescue him. His mockery had put others at risk, and his survival had cost the community not just in herbs and care, but in the spiritual debt now owed for violating sacred space.

When he could finally walk again, limping heavily on his scarred leg, Si Malang made his way to the river’s edge. He carried offerings of rice, flowers, and fruit. With tears streaming down his face, he placed them carefully by the water and bowed deeply.

“Forgive me,” he whispered to the river, to the spirits, to the guardian crocodile whose mercy had spared his life. “I was a fool. I mistook my small knowledge for wisdom, my limited sight for understanding. I will honor the taboos. I will respect the boundaries. I will teach my children what I should have learned from my elders.”

From that day forward, Si Malang became the most careful observer of river traditions. His near death experience had taught him what no amount of reasoning could: that some wisdom transcends understanding, that respect need not require full comprehension, and that inherited knowledge often contains truths deeper than surface logic can grasp.

He taught other young fishermen not just the practical skills of the trade but also the spiritual protocols that kept them safe. When he spoke of the guardian crocodile, his voice carried the weight of personal testimony, and young people listened with attention they might not have given to mere tradition.

The scars on his leg served as permanent reminders of the cost of arrogance and the gift of a second chance. Si Malang lived many more years, becoming in time an elder himself, one who understood that true wisdom lies not in dismissing what we don’t understand but in respecting the accumulated knowledge of those who came before us.

And in the forbidden pool near the river’s bend, the great crocodile continued its ancient watch, guardian and spirit, creature and keeper of boundaries, reminding all who saw it that some places are sacred not because we make them so but because they have always been, and will remain so long after we are gone.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

The legend of Si Malang and the river crocodile teaches us that arrogance and dismissal of inherited wisdom can have devastating consequences. Traditional taboos and spiritual practices often contain practical wisdom accumulated over generations, and respecting them is not superstition but prudent acknowledgment of knowledge deeper than individual understanding. The story emphasizes that our actions affect not only ourselves but also those around us, and that pride which endangers others is a particularly grave failing.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Si Malang in this Malaysian folk tale? A: Si Malang is an arrogant fisherman who repeatedly ignores river taboos and mocks traditional beliefs about guardian spirits and sacred boundaries. His name means “unfortunate,” and he represents the danger of pride that dismisses inherited wisdom. His character demonstrates how overconfidence in one’s own understanding can lead to disaster when it blinds us to accumulated knowledge and spiritual realities.

Q2: What are the river taboos that Si Malang ignores? A: The river taboos include avoiding fishing in certain sections during specific moon phases, never swimming in the forbidden deep pool near the river’s bend, and making regular offerings of rice and flowers to honor the river spirits and their crocodile guardians. These rules represent the accumulated wisdom about respecting sacred spaces and maintaining harmony between humans and the spiritual forces inhabiting nature.

Q3: What role do the guardian crocodiles play in Malaysian river folklore? A: The guardian crocodiles are both physical animals and spiritual beings that protect sacred river boundaries. They are believed to be inhabited by river spirits, serving as enforcers of taboos and keepers of sacred spaces. They represent the dual nature of dangerous wildlife as both natural creatures requiring practical caution and spiritual guardians requiring respectful acknowledgment of their sacred role.

Q4: How does Si Malang’s arrogance endanger others? A: Si Malang’s open mockery of the river spirits and deliberate violation of taboos forces young men from his village to risk their lives rescuing him when the guardian crocodile attacks. His actions create spiritual debt for the community and demonstrate how individual disrespect for sacred boundaries can have consequences that extend beyond the offender to affect innocent others who feel obligated to help.

Q5: What causes Si Malang’s transformation from skeptic to believer? A: Si Malang’s near death experience with the guardian crocodile, combined with the realization that his arrogance endangered the young men who saved him, causes his transformation. The physical scars and emotional trauma force him to recognize that his limited understanding does not encompass all truth, and that inherited wisdom contains knowledge more profound than individual rationalization can grasp.

Q6: What does this story teach about traditional knowledge in Malaysian culture? A: This Malaysian folk tale teaches that traditional taboos and spiritual practices represent accumulated wisdom that should be respected even when not fully understood by contemporary rational thinking. It emphasizes that indigenous knowledge about nature, sacred spaces, and spiritual boundaries often contains practical safety wisdom wrapped in spiritual language. The story warns that dismissing tradition as mere superstition reflects dangerous arrogance rather than enlightened thinking.

Source: Adapted from Malaysian oral folklore traditions.

Cultural Origin: Malaysia, Southeast Asia.