In the shadow of the great mountain of Spin Ghar, where the ridges glow silver at dawn and the valleys shift from green to gold with the turning seasons, two clans lived side by side in uneasy balance. Clan A grazed their herds on the southern slopes, Clan B on the northern. Though peace had held for many years, it was a peace as fragile as frost on morning grass, beautiful, but easily broken.

One summer afternoon, as shepherds guided their flocks toward a shared grazing stream, a heated argument erupted. Wakil, a young warrior of Clan A known for his calm strength, confronted Qadir of Clan B over stray goats that had crossed into their land. Harsh words became threats. Qadir, hot-tempered and proud, struck Wakil across the face with the back of his hand.

Discover more East Asian Folktales from the lands of dragons, cherry blossoms, and mountain spirits.

Among the Pashtun tribes, an insult delivered publicly is not just a wound to pride, it is a wound to one’s honour, one that the code of Pashtunwali demands be answered. According to ancient custom, Wakil had two choices: demand a public apology or deliver equal retribution.

Wakil sought peace first. He stood before Qadir and said, “Let our fathers rest in peace. Apologize before our people so this matter ends here.”

But Qadir refused.

“Not even the mountain can make me kneel,” he declared.

The elders gathered, proposing nanawatai, the traditional ritual of forgiveness in which a man kneels at the offended family’s doorway to ask for peace. But Qadir rejected even this sacred act. His stubbornness sealed the path ahead: a feud became unavoidable.

Soon after, violence erupted. Under cover of twilight, men of Clan B ambushed Wakil’s household. Two of Wakil’s cousins were killed defending the family compound, and the courtyard walls were marked with the scars of that night. Wakil, though wounded, survived.

Grief carved new depth into the young warrior’s spirit. The laws of honour now placed a burden upon him: a blood-debt, wajib—an obligation. The entire clan awaited his decision. His uncles urged him to strike swiftly. His peers sharpened their blades. The funeral wails had barely faded from the air.

But Wakil hesitated.

His mother, a stern woman whose eyes carried the wisdom of many winters, placed her hands on his shoulders.

“My son,” she whispered, “blood washes blood, but no river runs forever. Men who kill easily become slaves to the past. Think, before the mountain weighs your heart.”

For days, Wakil wrestled with his duty. Honour demanded vengeance, yet something deeper, older, perhaps wiser, pulled him toward restraint. But when he heard that Qadir had fled into the mountain passes, he strapped on his sword and set out alone. The clans believed he had gone to complete the debt. Only Wakil knew he had gone to find something else: truth.

The trail led upward into a perilous frost-lit pass. Snow had begun to gather in the crevices, and the wind carried the sharp scent of winter. As Wakil approached a narrow ridge, he heard a child’s cry carried on the wind, sharp, frightened, desperate.

He hurried toward the sound and found a sight that froze him in place.

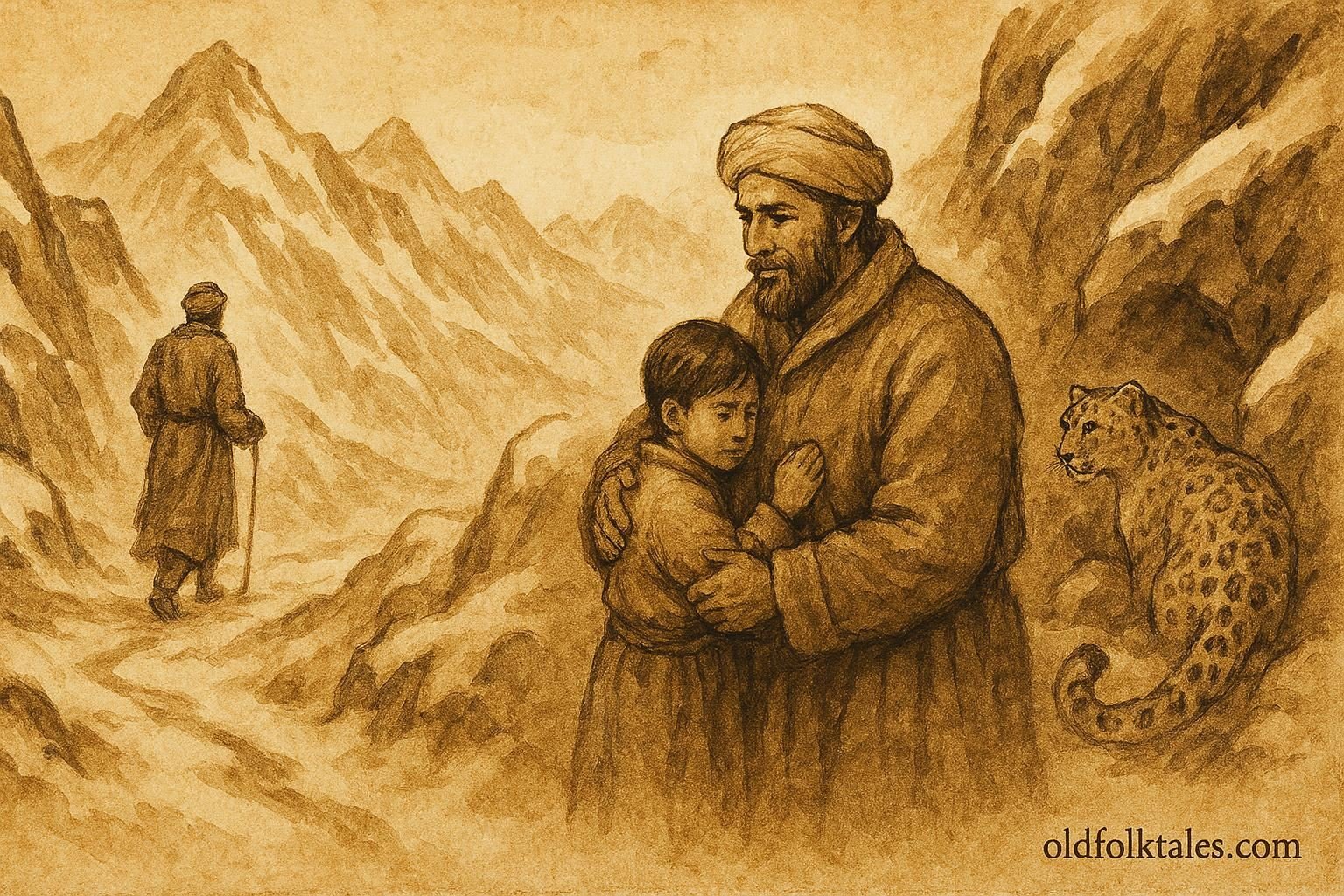

Qadir stood with his cloak wrapped around a trembling child, his nephew, while a snow leopard, sleek and white like a living ghost, circled them. The animal’s muscles rippled with intent, its tail swaying low.

Wakil had come seeking the man who killed his cousins. Instead, he found that same man shielding a child with his own life.

Without hesitation, Wakil drew his blade, not toward Qadir, but toward the beast. Together, the two men drove the leopard back with shouts and flashing steel until it disappeared among the rocks.

Silence fell. Only the mountain wind moved.

Qadir lowered the frightened child, then turned to Wakil. Slowly, almost painfully, he bent to his knees.

“I who once swore I would never kneel,” he said, voice breaking, “now place my life in your hands. Take what is owed. End this.”

Wakil looked at the man kneeling before him, at the child clinging to Qadir’s sleeve, and at the mountains rising like eternal witnesses around them. Then he sheathed his sword.

“Let the mountain witness,” he said softly. “This life is returned to God, not taken by man.”

When they descended, the elders gathered. After hearing the tale, they declared the blood-debt fulfilled, not through violence, but through mercy that required greater courage than any blade. The two clans forged a new pact, setting clear boundaries and seasonal routes. Feasts were held in both villages. Children from the once-rival clans played together in the foothills.

And ever since, when disputes threatened to ignite across the Pashtun lands, elders recited the tale of Wakil and Qadir, the story of the man who chose honour without bloodshed, bravery without cruelty, and mercy without weakness.

Journey through enchanted forests and islands in our Southeast Asian Folktales collection.

Moral Lesson

This Pashtun folktale teaches that true bravery is not in striking quickly, but in choosing the harder path of mercy. Honour rooted in compassion creates peace that swords alone can never win.

Knowledge Check

1. What is the central conflict in The Blood-Debt of Spin Ghar?

A dispute between two Pashtun clans escalates after an insult violates the code of honour.

2. What cultural code shapes the characters’ actions?

The Pashtunwali code, emphasizing honour, apology, and rightful retribution.

3. What symbolic meaning does Spin Ghar mountain carry?

It represents witness, permanence, and the weight of ancestral law in Pashtun culture.

4. Why is Wakil’s final choice significant?

He resolves a blood-debt through mercy, transforming the meaning of honour.

5. What lesson does the story highlight about bravery?

That true bravery includes restraint, compassion, and moral strength.

6. What region does the folktale belong to?

The Pashtun region spanning Afghanistan–Pakistan.

Source: Traditional Pashtun oral folklore.

Cultural Origin: Afghanistan–Pakistan (Pashtun Region)