In the vast plains of Isan, the northeastern region of Thailand where the Mekong River marks the border with Laos and the land stretches flat and golden beneath endless skies, the people have always lived in close harmony with the rhythms of nature. Their rice fields depend on the monsoon rains, their festivals follow the agricultural calendar, and their stories speak of spirits that dwell in trees, rivers, and sacred places. Among all these tales, one stands out as both beloved and bittersweet: the legend of the great white elephant of Phaya Thaen.

Long ago, in a time when the kingdoms of Siam were still forming and the people of Isan lived in scattered villages connected by dusty paths through the forest, there appeared in the region a magnificent white elephant. The creature was unlike any elephant the villagers had ever seen: its hide was not gray but pure white, gleaming like polished ivory in the sunlight, and it stood taller than any barn, its tusks curved and elegant as the crescent moon. Its eyes were gentle and wise, holding an intelligence that seemed almost human.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

The elephant appeared first at the edge of the forest near a village called Ban Phaya Thaen, named for an ancient spirit lord who was said to protect the region. The villagers were initially frightened: wild elephants could be dangerous, destroying crops and threatening lives when angered. But this white elephant showed no aggression. Instead, it moved peacefully through the rice paddies, careful not to damage the growing plants, drinking from the irrigation canals, and resting in the shade of the great tamarind trees that dotted the landscape.

The village elders consulted among themselves and with the local monks. A white elephant, they knew, was sacred in Buddhist tradition: a symbol of purity, wisdom, and royal blessing. In ancient times, white elephants were reserved for kings, believed to be manifestations of divine favor. That such a creature had come to their humble village seemed a sign of great significance.

“We must treat it with respect,” said the eldest monk, a venerable man named Phra Ajahn Somchai. “This is no ordinary elephant. I believe it is a guardian spirit, sent to watch over our fields and our people. We should make offerings and honor its presence.”

And so the villagers did. They left bundles of sugarcane and baskets of fruit at the forest’s edge. They built a small spirit house near where the elephant often appeared, making offerings of incense and flowers. The children were taught to bow respectfully when they saw the great white creature, and even the bravest young men gave it wide berth, not from fear but from reverence.

In return, the elephant seemed to guard the village and its surrounding fields. Wild boars that had plagued the rice paddies for years stopped coming. Tigers that occasionally prowled near the village boundaries were never seen again. The crops grew strong and healthy, and the village prospered. The people came to call the creature “Phaya Chang Phueak” (Lord White Elephant) and believed it was the earthly form of Phaya Thaen himself, the ancient guardian spirit manifested to protect them in a time of need.

For three years, this peaceful coexistence continued. The white elephant became part of village life, as familiar and reassuring as the temple bell that rang at dawn. Children grew up seeing it as they walked to school, farmers waved to it as they worked their fields, and the elderly spoke of it as a blessing that had transformed their fortunes.

But then came the year of the great drought.

The monsoon rains, which usually arrived like clockwork at the beginning of the wet season, failed to come. Week after week passed with clear, merciless skies. The sun beat down on the rice paddies, turning the mud to cracked earth. The irrigation canals ran dry. The rice seedlings, so carefully planted, withered and died. The villagers prayed at the temple, made offerings to the spirits, and performed the traditional rocket festival to call the rains, shooting bamboo rockets into the sky to wake the rain gods. But no rain came.

Famine threatened. Without rice, the villagers would have nothing to eat and nothing to sell. Desperation settled over Ban Phaya Thaen like a suffocating blanket. Children cried from hunger. The elderly grew weak. Even the monks in the temple had little food to sustain them.

It was during this darkest time that the white elephant performed its miracle.

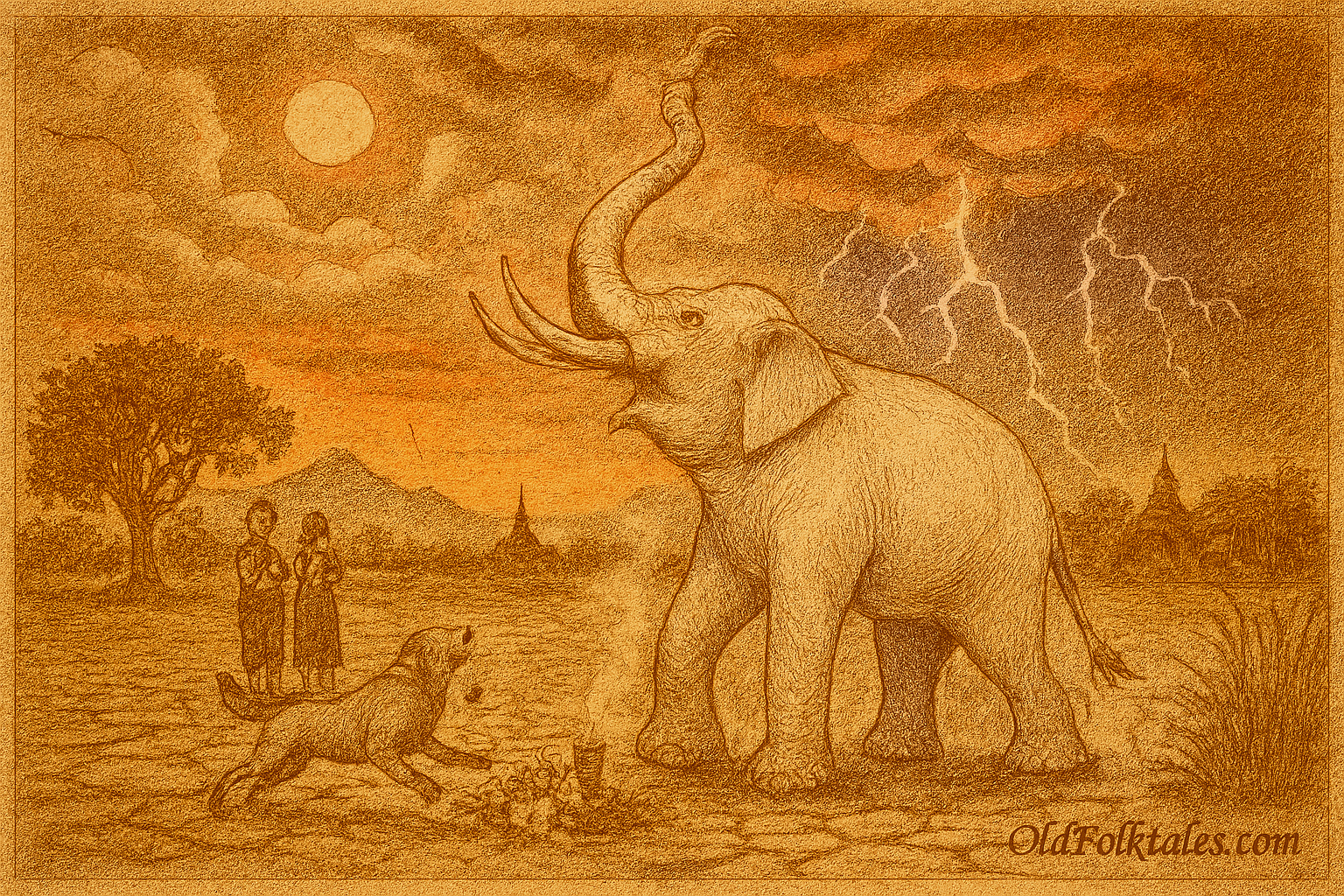

One dawn, as the sun rose over the parched landscape painting the sky in shades of orange and pink, the great white elephant emerged from the forest where it had been sheltering from the heat. It walked to the center of the largest rice field (now just cracked, barren earth) and raised its massive trunk to the sky. Then it trumpeted.

The sound was unlike anything the villagers had ever heard. It was not the typical call of an elephant but something deeper, more resonant: a sound that seemed to vibrate in the chest, in the bones, in the very earth itself. The trumpeting rolled across the plain like thunder, echoing from the hills in the distance, shaking the leaves of the tamarind trees.

The elephant trumpeted three times, each call louder and more powerful than the last, its trunk raised high as if calling to the heavens themselves.

And the heavens answered.

Within an hour, clouds began to gather on the horizon thick, dark monsoon clouds heavy with rain. They rolled across the sky faster than seemed natural, covering the sun, turning day to twilight. The wind picked up, carrying the scent of coming rain. Then, with a crack of lightning and a roll of thunder, the rains came.

They came in torrents, in sheets, in a deluge that filled the canals and soaked the earth and made the villagers run out of their houses laughing and crying with relief. The drought was broken. The fields could be replanted. The village was saved.

When the villagers looked for the white elephant to thank it, to make offerings in gratitude, they saw it standing in the rain, its white hide glistening with water, looking toward the sky as if in communication with forces beyond human understanding. In that moment, every person present knew with absolute certainty that they were witnessing not just an animal but a divine being, a spirit in elephant form that had called the rains through its sacred voice.

News of the miracle spread throughout Isan. People from neighboring villages came to see the white elephant and to ask for its blessing. The region’s prosperity returned, and with it came attention from the outside world.

Among those who heard the story was a provincial official named Khun Narong, a man of wealth and ambition who held a position in the regional government. Unlike the simple villagers, Khun Narong did not see the white elephant as a sacred guardian. He saw it as a prize: an exotic creature that could be captured and presented to the royal court in Bangkok, earning him favor and advancement.

Khun Narong was not a spiritual man. He dismissed the villagers’ stories of the elephant calling the rain as peasant superstition. To him, a white elephant was simply valuable property, and he intended to claim it.

He arrived at Ban Phaya Thaen with a company of armed men, carrying nets and chains. The villagers pleaded with him to leave the elephant in peace, explaining that it was their protector, their guardian spirit, but Khun Narong laughed at their concerns.

“It is only an animal,” he said dismissively. “And by law, all white elephants belong to the crown. I am authorized to capture it and bring it to the capital.”

The villagers could do nothing to stop him. Khun Narong was powerful, connected to the regional authorities, and backed by armed men. They could only watch in horror as the official and his hunters set out to trap the sacred elephant.

For two days, the hunting party tracked the white elephant through the forests and fields. The creature seemed to know it was being pursued, moving swiftly despite its size, always staying just out of reach. But Khun Narong was determined and ruthless. On the third day, they cornered the elephant in a grove of banyan trees, their nets ready, their weapons at hand.

The white elephant stood before them, majestic and calm, its wise eyes looking at Khun Narong with what the official would later describe, in his moments of nightmares, as profound sadness and disappointment.

Then it raised its trunk to the sky and trumpeted one final time.

The sound was deafening: a cry that seemed to contain grief, rage, and power beyond measure. Dark clouds gathered instantly overhead, and thunder cracked so loudly that several of the hunters fell to their knees in terror. Lightning struck the ground around them, close enough that they could feel its heat, smell the ozone in the air.

When the thunder and lightning ceased and the hunters dared to look up, the white elephant was gone. It had simply vanished, leaving no trace, no tracks, nothing to show it had ever been there except the memory of that final, earth-shaking trumpet call.

Khun Narong searched for days, but the elephant was never seen again in physical form. His dreams of glory and advancement shattered, he returned to his post, where his failure became a source of shame. Some say his hair turned white overnight from the terror of that experience. Others say he eventually sought ordination as a monk, trying to atone for his arrogance and greed.

But the white elephant did not completely leave the people of Isan.

From that year forward, every time the wet season approached and the first monsoon rains were about to break over the northeastern plains, the people would hear it: a deep, resonant sound like thunder, but different from ordinary thunder. It would roll across the sky at dawn, shaking the earth, preceding the first rains by only hours.

“That is Phaya Chang Phueak,” the elders would say, teaching their grandchildren. “That is the voice of our guardian, calling the rains still, watching over us from the spirit world. The white elephant never truly left. It just transformed, becoming one with the thunder itself.”

To this day, in the villages of Isan, when the characteristic thunder of the early wet season rolls across the plains at dawn, farmers smile and make a wai gesture of respect toward the sky. They know the rains will come soon, that their fields will be blessed, that the guardian spirit of Phaya Thaen still watches over them.

And they teach their children never to mistake power for ownership, never to confuse sacred things with mere property, and never to forget that some beings are too divine to be captured: they can only be honored, respected, and allowed to fulfill their purpose freely.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

This legend teaches that divine blessings cannot be possessed or controlled by human ambition. The white elephant’s disappearance when faced with greed shows that sacred things vanish when approached with wrong intentions. Yet the story also reveals that true spiritual guardianship transcends physical form: the elephant became the thunder itself, continuing to bless those who honored it while remaining forever beyond the reach of those who would exploit it.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What was the significance of the white elephant in Thai Buddhist and Isan culture? A: In Thai Buddhist tradition, white elephants are sacred symbols of purity, wisdom, and divine blessing, historically reserved for royalty. The white elephant of Phaya Thaen was believed to be a manifestation of the guardian spirit Phaya Thaen himself, appearing in physical form to protect the village and its rice fields during a time of need.

Q2: How did the white elephant save the village from famine? A: During a devastating drought when the monsoon rains failed to come and crops were dying, the white elephant walked to the center of the rice fields at dawn and trumpeted three times toward the sky. Its call was so powerful it seemed to shake the earth, and within an hour, monsoon clouds gathered and rain poured down, breaking the drought and saving the village from starvation.

Q3: Who was Khun Narong and what was his mistake in the legend? A: Khun Narong was a wealthy, ambitious provincial official who heard about the white elephant and wanted to capture it to present to the royal court for personal advancement. His mistake was seeing the sacred guardian as mere property to be owned rather than a divine being to be revered. His greed and lack of spiritual understanding led to the elephant’s disappearance.

Q4: What happened when Khun Narong tried to capture the white elephant? A: When Khun Narong and his hunters cornered the elephant in a banyan grove, the creature trumpeted one final time with such power that thunder cracked, lightning struck around them, and dark clouds gathered instantly. When the thunder ceased, the white elephant had completely vanished, leaving no trace behind, and was never seen in physical form again.

Q5: How does the elephant spirit continue to protect Isan villages today? A: According to the legend, the white elephant transformed into the thunder itself. Every year at the start of the wet season, villagers hear a distinctive thunder at dawn that rolls across the plains different from ordinary thunder which they recognize as the voice of Phaya Chang Phueak calling the rains. This thunder signals that the monsoon rains will soon arrive to bless their fields.

Q6: What cultural values does this Isan legend teach about nature and the sacred? A: The legend emphasizes that sacred and divine beings deserve reverence, not exploitation; that nature’s guardians protect those who respect them; that greed and the desire to possess spiritual things leads to loss; and that true blessings come through proper relationship with the sacred, not through ownership or control. It teaches the Isan values of humility before nature, respect for guardian spirits, and understanding that some things are meant to remain free and wild.

Cultural Origin: Isan region (Northeastern Thailand)