Long before Mount Popa became renowned as the dwelling place of the thirty-seven nats, before pilgrims climbed the seven hundred seventy-seven steps to the golden shrines, before the mountain became the spiritual heart of Myanmar, there existed a clan of monkeys whose wisdom rivaled that of the monks who would later build their monasteries upon the volcanic slopes.

Mount Popa rose from the Myingyan Plain like a mystical island in a sea of green, its volcanic peak reaching toward the heavens, perpetually crowned with clouds. The mountain was ancient even when the world was young, and its slopes were thick with teak forests where shadows moved with lives of their own. But what made Mount Popa truly sacred were the springs crystal-clear waters that flowed from deep within the mountain’s heart, waters that never ran dry even in the harshest drought, waters that were said to hold the essence of the earth itself.

Click to read all East Asian Folktales — including beloved stories from China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia.

These springs were guarded by a remarkable clan of monkeys. They were not like the chattering, mischievous creatures found in ordinary forests. These monkeys moved with deliberate grace, their eyes reflecting an intelligence that made travelers pause and wonder. Their fur bore the reddish-gold color of temple offerings, and they conducted themselves with a dignity that commanded respect. The eldest among them, a great silver-backed patriarch whose face bore the lines of countless seasons, was said to be older than the oldest living person in the valley below.

The monkey clan understood their sacred duty. They maintained the purity of the springs, clearing fallen leaves and branches from the pools, chasing away serpents and other creatures that might pollute the waters. They kept watch over the mountain’s secrets, observing all who came and went, distinguishing between those who approached with reverence and those who came with ill intent. The villagers who lived at the mountain’s base knew to leave offerings of fruit and flowers at the forest’s edge, tokens of gratitude for the monkeys’ stewardship of the life-giving waters.

Stories were told of how the monkeys would guide lost travelers to safety, appearing suddenly on the path when fog descended, leading confused pilgrims away from dangerous cliffs and toward secure shelter. Other tales spoke of how they would gather medicinal plants and leave them near the huts of sick villagers, silently providing remedies that local healers had failed to obtain. The people understood that these were no ordinary animals, but servants of the mountain spirits themselves intermediaries between the mortal realm and the domain of the nats.

Among the villagers, there lived a hunter named Kyaw Htun, a man whose skill with the bow was matched only by his arrogance. He was tall and strong, with arms that could draw the heaviest bow and eyes sharp enough to spot a deer at impossible distances. But Kyaw Htun possessed a cruel streak that darkness loves to feed upon. Where other hunters killed only what they needed for food and survival, he killed for sport, for pleasure, for the simple joy of watching life flee from dying eyes.

Kyaw Htun had heard the stories of the sacred monkeys, and they filled him with contempt. “Spirits? Servants of nats?” he would scoff, spitting betel juice onto the ground. “They are merely clever beasts. Nothing more. The fools of this village worship animals while I prove myself the master of all creatures.”

One day, consumed by his desire to demonstrate his superiority and mock what he saw as the villagers’ foolish superstitions, Kyaw Htun devised a wicked plan. He would show everyone that the sacred monkeys were not protected by spirits, that they were vulnerable and ordinary despite all the reverence they received. He would poison them not all at once, but slowly, mixing toxins into fruits he would leave near the springs. It would be, he thought with dark amusement, entertaining to watch the so-called wise creatures sicken and die.

He spent several days preparing his poison, grinding toxic plants and mixing them with sweet palm sugar to mask the bitter taste. He placed the poisoned fruit in a basket woven from bamboo and set out before dawn, climbing the mountain path with the confidence of one who believed himself beyond the reach of consequence.

The morning was strange. The usual bird songs were absent, and an unusual silence hung over the forest like a held breath. The leaves, normally rustling with mountain breezes, hung perfectly still. But Kyaw Htun, blinded by arrogance, noticed nothing amiss.

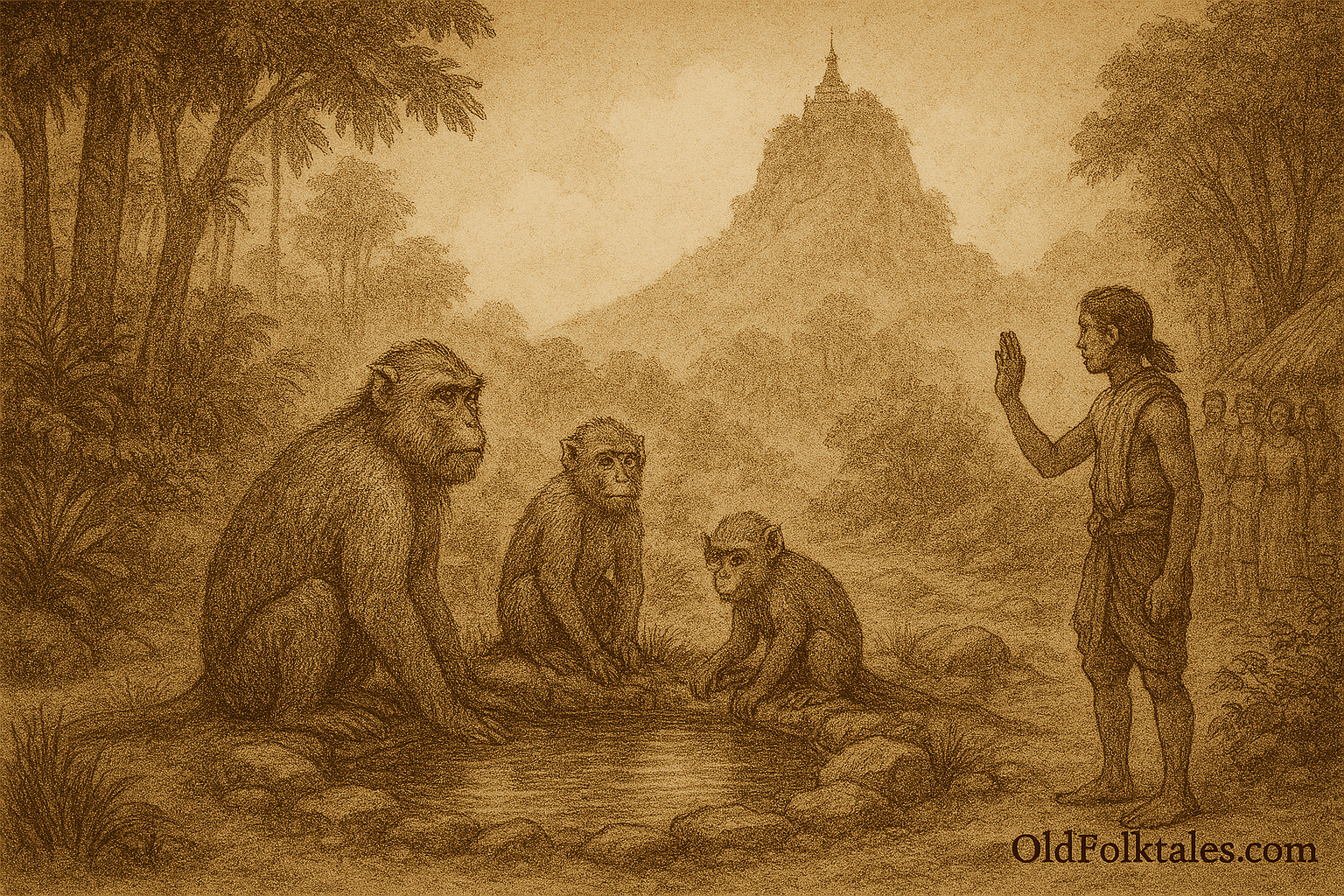

He reached the sacred springs just as the sun broke over the distant horizon. The monkeys were there, as they always were, sitting in a semicircle around the largest pool, their morning meditation undisturbed. The silver-backed patriarch sat at the center, his eyes closed, his breathing slow and rhythmic. The other monkeys surrounded him, young and old, all perfectly still in their contemplation.

Kyaw Htun smirked at the sight. “Perfect,” he whispered, setting down his basket of poisoned fruit. “Eat well, wise ones. Let us see how sacred you truly are.”

But as he placed the first piece of tainted fruit near the water’s edge, the sky darkened with supernatural speed. Clouds black as obsidian and roiling with barely contained fury gathered above Mount Popa’s peak. The temperature dropped so suddenly that Kyaw Htun’s breath became visible in the air. The silence of the forest was broken by a low rumble, not quite thunder, but something deeper and more primal.

The patriarch monkey opened his eyes and looked directly at Kyaw Htun. In that gaze, the hunter saw something that froze the blood in his veins not animal intelligence, but consciousness ancient and vast, awareness that had witnessed the mountain’s birth and would see its eventual return to dust.

The storm struck with the force of divine wrath. Lightning cracked across the sky, not randomly but with purpose, striking the trees around Kyaw Htun in a deliberate circle, trapping him within a ring of scorched earth. The wind rose to a shriek, tearing at his clothes and hair. Rain fell in sheets so thick he could barely breathe.

Kyaw Htun reached for his bow and arrows, some animal instinct telling him to defend himself though he knew not what he was defending against. But when his fingers closed around an arrow shaft, it crumbled in his hand like ancient parchment. He pulled another from his quiver the same result. The wood had become brittle, desiccated, as if centuries had passed in mere moments. Every arrow in his possession turned to dust at his touch, his greatest weapons rendered useless by forces he could neither see nor comprehend.

The basket of poisoned fruit burst into flames despite the pouring rain, the toxic offerings consumed by fire that burned with unnatural colors green and purple and blue. The flames spread to nothing else, contained within the basket until every piece of fruit was reduced to ash, the poison neutralized and the evil intent cleansed.

Kyaw Htun fell to his knees, his arrogance shattered like his arrows. The monkeys had not moved. They sat in their semicircle, watching him with eyes that held no malice, only an ancient sadness for a creature who had forgotten his place in the grand design of existence.

The storm lasted until every trace of poison had been purged from the mountain. Then, as suddenly as it had appeared, it ceased. The clouds parted, revealing a sky of brilliant blue. Sunlight streamed through the teak forest, illuminating the springs until they glowed like liquid crystal.

The silver-backed patriarch rose and approached Kyaw Htun, who remained on his knees, trembling and soaked. The great monkey placed one weathered hand upon the hunter’s head not in blessing, but in acknowledgment. The gesture said: You have been shown the truth. What you do with this knowledge is your choice.

Kyaw Htun stumbled down the mountain, his bow abandoned, his quiver empty, his pride in ruins. When he reached the village, he could not speak of what had transpired. Some profound transformation had occurred within him. In the days that followed, he gave away his hunting weapons and spent his time in quiet service, carrying water for the elderly, repairing the monastery’s walls, sitting in meditation beneath the bodhi tree.

The monks who later built their shrines upon Mount Popa’s slopes learned the story from the elders. They understood what the villagers had always known that the monkeys were not merely guardians of the springs, but servants of the nats themselves, manifestations of the mountain’s protective spirits. The monkeys’ wisdom predated human settlement, their purpose woven into the very fabric of Mount Popa’s sacred nature.

To this day, the monkeys of Mount Popa are treated with profound reverence. Pilgrims climbing to the shrines offer them fruit and respect, never mockery. The springs still flow pure and clear, their waters still carry healing properties, and the monkey clan still maintains their eternal vigil. And sometimes, when the mist rises from the valleys and wraps the mountain in mystery, those with spiritual sight claim to see the monkeys glowing faintly with an inner light servants of the nats, guardians of the sacred, reminders that some things in this world exist beyond human understanding and demand our humility.

The brittle arrows of Kyaw Htun were never found, dissolved completely by forces that protected the mountain’s sanctity. But the lesson of his transformation was never forgotten, passed down through generations as a warning and a teaching: approach the sacred with reverence, for the spirits who guard Myanmar’s holy places suffer no disrespect, and the servants of the nats are more powerful than any mortal hunter’s pride.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Moral Lesson

The legend of the Monkeys of Mount Popa teaches us that arrogance and cruelty toward sacred beings and nature invite divine retribution. Kyaw Htun’s attempt to poison the guardian monkeys demonstrates how those who abuse their power and mock spiritual wisdom will find their weapons both literal and metaphorical turned to dust. The story emphasizes the importance of recognizing forces greater than ourselves and approaching the sacred with humility and respect. It illustrates that true wisdom lies in understanding our place within the natural and spiritual order, not in attempting to dominate it.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What made the monkeys of Mount Popa different from ordinary monkeys?

A: The Mount Popa monkeys moved with deliberate grace, possessed eyes reflecting deep intelligence, had reddish-gold fur like temple offerings, and conducted themselves with dignified wisdom. They were recognized as servants of the mountain spirits (nats) rather than ordinary animals.

Q2: What sacred duty did the monkey clan perform on Mount Popa?

A: The monkeys guarded the mountain’s sacred springs, maintaining water purity by clearing debris, chasing away creatures that might pollute the waters, guiding lost travelers to safety, and gathering medicinal plants for sick villagers.

Q3: Who was Kyaw Htun and what was his plan?

A: Kyaw Htun was an arrogant hunter skilled with the bow who killed for sport rather than necessity. He planned to poison the sacred monkeys with toxic fruit mixed with palm sugar to prove they weren’t spiritually protected and to mock the villagers’ beliefs.

Q4: What supernatural events occurred when Kyaw Htun tried to poison the monkeys?

A: A violent storm struck instantly with purposeful lightning, his arrows turned brittle and crumbled to dust when touched, the poisoned fruit burst into multicolored flames despite rain, and the patriarch monkey revealed ancient consciousness in his gaze.

Q5: How did Kyaw Htun’s life change after the mountain spirits’ intervention?

A: Kyaw Htun was profoundly transformed he abandoned his weapons, gave away his hunting tools, and devoted himself to humble service including carrying water for elders, repairing monastery walls, and practicing meditation under the bodhi tree.

Q6: What is the cultural significance of the monkeys in Myanmar’s nat worship tradition?

A: The monkeys represent intermediaries between the mortal realm and the nat spirit domain, serving as physical manifestations of the mountain’s protective forces. Their story reinforces Buddhist concepts of respecting all beings, recognizing spiritual hierarchy, and approaching sacred places with humility and reverence.

Source: Adapted from Myanmar Ministry of Culture, Popa Nat Oral History Compendium

Cultural Origin: Mount Popa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar